Code along video

Although we strongly suggest coding along with us by following the video above, you can find completed code from the code along in our course code repository.

Learning objectives

We are now ready to return to our second main narrative in this chapter, finding prime numbers. In the preceding lesson, we saw that Euclid’s algorithm offers a substantial and surprising improvement over a trivial approach. How will the sieve of Eratosthenes fare against a simpler prime finding approach?

Below, we reproduce our pseudocode for TrivialPrimeFinder() and SieveOfEratosthenes() (along with necessary subroutines) from the main text. In this lesson, we will implement these two algorithms and time them.

TrivialPrimeFinder(n)

primeBooleans ← array of n+1 false boolean variables

for every integer p from 2 to n

if IsPrime(p) is true

primeBooleans[p] ← true

return primeBooleans

IsPrime(p)

if p < 2

return false

for every integer k between 2 and √p

if k is a divisor of p

return false

return true

SieveOfEratosthenes(n)

primeBooleans ← array of n+1 true boolean variables

primeBooleans[0] ← false

primeBooleans[1] ← false

for every integer p between 2 and √n

if primeBooleans[p] = true

primeBooleans ← CrossOffMultiples(primeBooleans, p)

return primeBooleans

CrossOffMultiples(primeBooleans, p)

n ← length(primeBooleans) - 1

for every multiple k of p (from 2p to n)

primeBooleans[k] ← false

return primeBooleans

Code along summary

Setup

Create a new folder called primes in your python/src directory, and then create a new file within the python/src/primes folder called main.py, which we will edit in this lesson.

In main.py, add the following starter code.

def main():

print("Prime finding.")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

The trivial prime finding algorithm

We are now ready to return to TrivialPrimeFinder() and use what we have learned about lists in the previous code along. Because we pass much of the work to a subroutine is_prime(), this function is quite short. Note that we raise a ValueError if n is less than zero.

def trivial_prime_finder(n: int) -> list[bool]:

"""

Returns a list of boolean variables storing the primality of each nonnegative integer up to and including n.

Parameters:

- n (int): an integer

Returns:

list[bool]: a list of boolean variables storing the primality of each nonnegative integer up to and including n.

"""

if n < 0:

raise ValueError("n must be nonnegative.")

prime_booleans = [False] * (n + 1)

for p in range(2, n + 1):

prime_booleans[p] = is_prime(p)

return prime_booleans

Testing whether a number is prime

We will need to implement is_prime() as well. To do so, we need to have a way to represent the pseudocode line

for every integer k between 2 and √p

To do so, we will use the math module in Python, which has a built in function sqrt(). Note that the second value given to range() is math.sqrt(p) + 1 instead of math.sqrt(p) because ranging in Python goes up to but not including the second element provided to range().

for k in range(2, math.sqrt(p) + 1):

We also know from our work with greatest common divisors in a previous code along that we can check whether k is a divisor of p by checking whether p%k is equal to zero. Our is_prime() function is shown below, which includes some tests when p is negative or less than 2.

import math # should appear at top of file

def is_prime(p: int) -> bool:

"""

Test if p is prime.

Parameters:

- p (int): an integer

Returns:

bool: True if p is prime and False otherwise.

"""

if p < 0:

raise ValueError("Error: negative input given.")

if p < 2:

return False

for k in range(2, math.sqrt(p) + 1):

if p % k == 0:

return False

return True

Unfortunately, this version of is_prime() produces an error because range() takes an int as input. To fix this issue, we will cast the expression math.sqrt(p) + 1 to be an integer. In general, the expression int(x), given a float x as input, returns the integer part of x; for example, int(2.817) is equal to 2, and int(-3.4) is equal to -3.

import math # should appear at top of file

def is_prime(p: int) -> bool:

"""

Test if p is prime.

Parameters:

- p (int): an integer

Returns:

bool: True if p is prime and False otherwise.

"""

if p < 2:

return False

for k in range(2, int(math.sqrt(p)) + 1):

if p % k == 0:

return False

return True

Note: Instead ofint(math.sqrt(p)), we could use the functionmath.isqrt(p), which rounds the result of taking the square root ofpdown to the nearest integer.

Now that we have implemented is_prime(), let’s now call trivial_prime_finder() from def main() and ensure that everything is working properly.

def main():

print("Primes.")

prime_booleans = trivial_prime_finder(10)

print(prime_booleans)

STOP: Open a command line terminal and navigate into the folder containing your code by using the commandcd python/src/primes. Then run your code by executing(macOS/Linux) orpython3 main.pypython main.py(Windows). You should see[False, False, True, True, False, True, False, True, False, False, False]printed to the console. This is correct becauseprime_booleans[2],prime_booleans[3],prime_booleans[5], andprime_booleans[7]should beTrueto correspond to the primality of 2, 3, 5, and 7 (see figure below).

i | prime_booleans[i] |

| 0 | False |

| 1 | False |

| 2 | True |

| 3 | True |

| 4 | False |

| 5 | True |

| 6 | False |

| 7 | True |

| 8 | False |

| 9 | False |

| 10 | False |

prime_booleans[i] for an array of length 11.Implementing the sieve of Eratosthenes

We are now ready to implement the sieve of Eratosthenes. Below, we reproduce the pseudocode for SieveOfEratosthenes() as well as its subroutine CrossOffMultiples().

SieveOfEratosthenes(n)

primeBooleans ← array of n+1 true boolean variables

primeBooleans[0] ← false

primeBooleans[1] ← false

for every integer p between 2 and √n

if primeBooleans[p] = true

primeBooleans ← CrossOffMultiples(primeBooleans, p)

return primeBooleans

CrossOffMultiples(primeBooleans, p)

n ← length(primeBooleans) - 1

for every multiple k of p (from 2p to n)

primeBooleans[k] ← false

return primeBooleans

Let us recall how the sieve of Eratosthenes works, as illustrated in the figure below. It first assumes that every integer is prime. Then, over a sequence of steps, it identifies the smallest number in the table that is not composite, and then it “crosses off” all of that number’s factors larger than itself (i.e., sets them to be composite), which is the work of CrossOffMultiples()

Like trivial_prime_finder(), we will need to declare prime_booleans as a list of boolean variables. We know that this list will have length n+1, and so we can declare it to have n+1 True values using the notation prime_booleans = [True] * (n + 1) that we introduced in the previous code along. Let’s start writing our function below.

def sieve_of_eratosthenes(n: int) -> list[bool]:

"""

Returns a list of boolean variables storing the primality of each nonnegative integer up to and including n,

implementing the "sieve of Eratosthenes" algorithm.

Parameters:

- n (int): an integer

Returns:

list: a list of boolean variables storing the primality of each nonnegative integer up to and including n.

"""

if n < 0:

raise ValueError("n must be nonnegative.")

prime_booleans = [True] * (n + 1)

# the meat of our function will go here

return prime_booleans

We can now initialize prime_booleans[0] and prime_booleans[1] to False.

def sieve_of_eratosthenes(n: int) -> list[bool]:

"""

Returns a list of boolean variables storing the primality of each nonnegative integer up to and including n,

implementing the "sieve of Eratosthenes" algorithm.

Parameters:

- n (int): an integer

Returns:

list[bool]: a list of boolean variables storing the primality of each nonnegative integer up to and including n.

"""

if n < 0:

raise ValueError("n must be nonnegative.")

prime_booleans = [True] * (n + 1)

prime_booleans[0] = False

prime_booleans[1] = False

# the meat of our function will go here

return prime_booleans

We are now ready to implement the engine of the sieve. We use a for loop to range over all p between 2 and √n; note below that we need to cast p ** 0.5 + 1 to have type int as we did in trivial_prime_finder().

def sieve_of_eratosthenes(n: int) -> list[bool]:

"""

Returns a list of boolean variables storing the primality of each nonnegative integer up to and including n,

implementing the "sieve of Eratosthenes" algorithm.

Parameters:

- n (int): an integer

Returns:

list[bool]: a list of boolean variables storing the primality of each nonnegative integer up to and including n.

"""

if n < 0:

raise ValueError("n must be nonnegative.")

prime_booleans = [True] * (n + 1)

prime_booleans[0] = False

prime_booleans[1] = False

# now, range over primeBooleans, and cross off multiples of first prime we see, iterating this process.

for p in range(2, int(math.sqrt(n)) + 1):

# in progress

return prime_booleans

Each time through the loop, we ask “Is p prime?” If this is the case (i.e., if prime_booleans[p] is True), then we keep prime_booleans[p] equal to True. We then update our prime_booleans list by looking for all other indices of prime_booleans that are multiples of p, and setting their corresponding values equal to False. We pass off this task to a subroutine cross_off_multiples().

def sieve_of_eratosthenes(n: int) -> list[bool]:

"""

Returns a list of boolean variables storing the primality of each nonnegative integer up to and including n,

implementing the "sieve of Eratosthenes" algorithm.

Parameters:

- n (int): an integer

Returns:

list[bool]: a list of boolean variables storing the primality of each nonnegative integer up to and including n.

"""

if n < 0:

raise ValueError("n must be nonnegative.")

prime_booleans = [True] * (n + 1)

prime_booleans[0] = False

prime_booleans[1] = False

# now, range over primeBooleans, and cross off multiples of first prime we see, iterating this process.

for p in range(2, int(math.sqrt(n)) + 1):

# is p prime? If so, cross off its multiples

if prime_booleans[p]:

prime_booleans = cross_off_multiples(prime_booleans, p)

return prime_booleans

Our function sieve_of_eratosthenes() is now complete, and we can turn to implementing cross_off_multiples(). This function takes a list prime_booleans of boolean variables as input, along with an integer p. It returns the updated list after setting prime_booleans[k] equal to False for every index k that is both larger than p and a multiple of p. We provide the function signature and docstring below, along with some parameter checking.

def cross_off_multiples(prime_booleans: list[bool], p:int) -> list[bool]:

"""

Returns an updated list in which all variables in the list whose indices are multiples of p (greater than p) have

been set to false.

Parameters:

- prime_booleans (list): a list of boolean variables storing the primality of each nonnegative integer

- p (int): an integer

Returns:

list[bool]: a list of boolean variables storing the primality of each nonnegative integer up to and including n with

multiples of p (greater than p) set to false.

"""

if len(prime_booleans) < 3:

raise ValueError("Error: insufficiently long boolean prime array.")

if p < 2:

raise ValueError("Error: invalid value given for p.")

# To fill in

We next want to find all indices k that are both larger than p and a multiple of p, which we can do by ranging from 2*p to (not including) n+1, using a step size of p. This can be achieved using for k in range(2 * p, n + 1, p):, as we learned about when discussing for loops.

def cross_off_multiples(prime_booleans: list[bool], p:int) -> list[bool]:

"""

Returns an updated list in which all variables in the list whose indices are multiples of p (greater than p) have

been set to false.

Parameters:

- prime_booleans (list): a list of boolean variables storing the primality of each nonnegative integer

- p (int): an integer

Returns:

list[bool]: a list of boolean variables storing the primality of each nonnegative integer up to and including n with

multiples of p (greater than p) set to false.

"""

if len(prime_booleans) < 3:

raise ValueError("Error: insufficiently long boolean prime array.")

if p < 2:

raise ValueError("Error: invalid value given for p.")

for k in range(2 * p, n + 1, p):

prime_booleans[k] = False

return prime_booleans

STOP: Let’s updatemain()with the code below. What happens when we callsieve_of_eratosthenes()?

def main():

print("Primes.")

prime_booleans = sieve_of_eratosthenes(10)

print(prime_booleans)

Unfortunately, when we call sieve_of_eratosthenes(), we obtain a NameError telling us that n is undefined in the line

for k in range(2 * p, n + 1, p):

When we declare prime_booleans within sieve_of_eratosthenes(), we use an input parameter n and construct prime_booleans to have length n+1. However, this parameter’s scope is confined to sieve_of_eratosthenes(), and cross_off_multiples() cannot see it. Fortunately, because we know that the length of prime_booleans is 1 larger than n, we can infer that n is equal to the length of prime_booleans minus 1. This brings us to a final implementation of cross_off_multiples() in which we first set n = len(prime_booleans) - 1.

def cross_off_multiples(prime_booleans: list[bool], p:int) -> list[bool]:

"""

Returns an updated list in which all variables in the list whose indices are multiples of p (greater than p) have

been set to false.

Parameters:

- prime_booleans (list): a list of boolean variables storing the primality of each nonnegative integer

- p (int): an integer

Returns:

list[bool]: a list of boolean variables storing the primality of each nonnegative integer up to and including n with

multiples of p (greater than p) set to false.

"""

if len(prime_booleans) < 3:

raise ValueError("Error: insufficiently long boolean prime array.")

if p < 2:

raise ValueError("Error: invalid value given for p.")

n = len(prime_booleans) - 1

for k in range(2 * p, n + 1, p):

prime_booleans[k] = False # k is composite

return prime_booleans

STOP: Make sure thatsieve_of_eratosthenes()is working now by calling it on an input of 10 and printing out the resulting list and ensuring that you get the same result that we did when callingtrivial_prime_finder().

Timing the two prime finding algorithms

Now that we have implemented two prime finding algorithms, we should time them as we did when comparing our GCD algorithms in a previous code along, in which we identify the runtimes of each algorithm and compute the “speedup” as the ratio of the time taken by the trivial approach to that of the sieve of Eratosthenes. We can time the two functions for a given value of n (which we set equal to 1,000,000) by updating def main() as well as the import statements for main.py as follows. Note that, to run the following code, we need to import the time module.

import time

def main():

n = 1000000

# timing trivial_prime_finder

start = time.time()

trivial_prime_finder(n)

elapsed_trivial = time.time() - start

print(f"trivial_prime_finder took {elapsed_trivial:.6f} seconds")

# timing sieve_of_eratosthenes

start = time.time()

sieve_of_eratosthenes(n)

elapsed_sieve = time.time() - start

print(f"sieve_of_eratosthenes took {elapsed_sieve:.6f} seconds")

# compute and print speedup

if elapsed_sieve > 0:

speedup = elapsed_trivial / elapsed_sieve

print(f"Speedup: {speedup:.2f}x faster")

STOP: Run this code, either on your computer or by using the window below. Try changingnto have smaller and larger values. What do you find?

Once again, as the table below demonstrates, we see an astonishing speedup over a trivial algorithm provided by a simple mathematical insight. In this case, why that insight even provides an insight is quite subtle. Rather than checking that each integer is prime, we save a great deal of time by crossing off the multiples of known primes. In one subroutine call, for example, we cross off half the integers up to n corresponding to every multiple of 2, without needing to call is_prime() on all these integers.

| n | trivial_prime_finder() Runtime | sieve_of_eratosthenes() Runtime | Speedup |

| 10,000 | 0.0133 s | 0.000871 s | 15 |

| 100,000 | 0.226 s | 0.00990 s | 23 |

| 1,000,000 | 5.01 s | 0.104 s | 48 |

| 10,000,000 | 0.930 s | 60 |

trivial_prime_finder() and sieve_of_eratosthenes() for a variety of values of the input value n, as well as the speedup in each case.Listing primes exemplifies appending to lists in Python

Although we have implemented algorithms to find all prime numbers, there is nevertheless something unsatisfying about what we have done because we are assigning boolean variables to all integers, but we are not producing a list of primes. This task can be completed easily once we have computed prime_booleans — we just need to create a list containing all integers p such that prime_booleans[p] is True.

In fact, we mentioned this task in the core text when introducing prime finding algorithms. At that time, we discussed a pseudocode function ListPrimes() that would call SieveOfEratosthenes() as a subroutine and then produce this list by using a function append() that takes an array of integers primeList and an integer p and adds p to the end of primeList.

ListPrimes(n)

primeList ← array of integers of length 0

primeBooleans ← SieveOfEratosthenes(n)

for every integer p from 0 to n

if primeBooleans[p] = true

primeList ← append(primeList, p)

return primeList

Python has exactly such a function append(), which applies to lists because (unlike tuples) lists are mutable. Given a list a and an item val that we wish to append to a, we can do so by calling

a.append(val)

We will use this idea to implement ListPrimes() as the following Python function list_primes(), which relies on sieve_of_eratosthenes() as a subroutine. This function illustrates a general theme of programming with lists that we introduced briefly in the previous code along, which is that if we don’t know in advance how long a list needs to be, we can initiate the list to have length 0 and append to it each time we need to add an element to the list.

def list_primes(n: int) -> list[int]:

"""

List all prime numbers up to and (possibly) including n.

Parameters:

- n (int): an integer

Returns:

list[int]: a list containing all prime numbers up to and (possibly) including n.

"""

if n < 0:

raise ValueError("Error: negative integer given as input to function.")

# first, create an empty list

prime_list = []

prime_booleans = sieve_of_eratosthenes(n)

for p in range(len(prime_booleans)):

if prime_booleans[p]:

prime_list.append(p)

return prime_list

We can now call list_primes() within def main() to ensure that it works. The following code should print [2, 3, 5, 7, 11] to the console when we run main.py.

def main():

print("Primes.")

# code omitted for clarity

prime_list = list_primes(11)

print(prime_list)

Counting primes

Now that we can list primes, we can ask a deeper question that some may even find spiritual: how many primes are there?

To be more precise, in the core text, we learned that the answer to this question is, “Infinitely many!” And yet in computer science, we inherently inhabit the realm of the finite; as such, we reframe our question as how many primes there are up to (and including) some given integer n.

Mathematicians have given this quantity a name: the prime counting function π(n) (pronounced “pi of n”), defined as the number of primes less than or equal to n. For example, π(10) = 4 because there are four primes up to and including 10: 2, 3, 5, and 7.

To plot this function, we need a fast way to compute π(k) for every integer k between 1 and n. We can do so by implementing a function prime_count_array() that takes as input an integer n and returns an array pi of length n+1 in which pi[k] stores the number of primes encountered up to and including k.

This function, which is shown below, first calls sieve_of_eratosthenes(n) to obtain a list of boolean values storing the primality of each integer. It then ranges over that list, storing a running count in a variable prime_counter that contains how many True values (primes) have been encountered so far, which it stores as pi[k].

def prime_count_array(n: int) -> list[int]:

"""

Produces a list storing the number of primes encountered up to a given integer.

Parameters:

- n (int)

Returns:

list[int]: list having length n+1 whose k-th element is equal to the number of primes less than or equal to k

"""

if n < 0:

raise ValueError("Error: negative integer given.")

prime_booleans = sieve_of_eratosthenes(n)

pi = [0] * (n + 1)

prime_counter = 0

for k, is_prime_val in enumerate(prime_booleans):

if is_prime_val:

prime_counter += 1

pi[k] = prime_counter

return pi

Plotting π(n) with matplotlib

We now wish to generate a line graph in which n is assigned to the x-axis and π(n) is assigned to the y-axis. To do so, we need to work with the popular plotting package Matplotlib. We can install Matplotlib using pip, the Python package installer, which is included in the installation of Python. To do so, open a command-line terminal and execute the following command:

pip3 install matplotlib

(On Windows, you may need to use pip instead of pip3.)

After intalling Matplotlib, add the import below at the top of main.py to import pyplot, an interface to Matplotlib that will make working with it easy. The phrase as pyplot means that we can refer to this package simply as pyplot throughout main.py.

import matplotlib.pyplot as pyplot

If we try to plot π(k) for every integer k up to (say) ten million, then the plot will contain millions of points and will be slow to draw. Instead, we will choose a step size (say, 100), and then plot π(2), π(102), π(202), and so on.

We will now write a function plot_primes() that takes as input integers n and step; this function does not return anything but produces our desired plot.

def plot_primes(n: int, step: int):

"""

Plots the prime counting function pi(n) as a line graph, sampling every 'step' x-values.

Parameters:

- n (int)

- step (int)

Output:

(nothing, produces plot)

"""

if n < 0 or step < 1:

raise ValueError("Invalid value given.")

First, we call prime_count_array(n) to generate the list pi storing the number of primes up to a given integer.

def plot_primes(n: int, step: int):

"""

Plots the prime counting function pi(n) as a line graph, sampling every 'step' x-values.

Parameters:

- n (int)

- step (int)

Output:

(nothing, produces plot)

"""

if n < 0 or step < 1:

raise ValueError("Invalid value given.")

# pi[k] = number of primes <= k

pi = prime_count_array(n)

To plot our line graph, pyplot demands lists of all x-values and all y-values included in the plot. The former are the values [, and the latter are the values of 2, 2+step, 2+2*step, ...]pi corresponding to these x-values.

def plot_primes(n: int, step: int):

"""

Plots the prime counting function pi(n) as a line graph, sampling every 'step' x-values.

Parameters:

- n (int)

- step (int)

Output:

(nothing, produces plot)

"""

if n < 0 or step < 1:

raise ValueError("Invalid value given.")

# pi[k] = number of primes <= k

pi = prime_count_array(n)

x_values = []

for x in range(2, n + 1, step):

x_values.append(x)

y_values = []

# for a given x, the y-value is pi(x), the number of primes that I have encountered thus far

for x in x_values:

y_values.append(pi[x])

We next create a figure that is 9 inches wide by 6 inches tall using pyplot.figure(), and we generate our plot using pyplot.plot().

def plot_primes(n: int, step: int):

"""

Plots the prime counting function pi(n) as a line graph, sampling every 'step' x-values.

Parameters:

- n (int)

- step (int)

Output:

(nothing, produces plot)

"""

if n < 0 or step < 1:

raise ValueError("Invalid value given.")

# pi[k] = number of primes <= k

pi = prime_count_array(n)

x_values = []

for x in range(2, n + 1, step):

x_values.append(x)

y_values = []

# for a given x, the y-value is pi(x), the number of primes that I have encountered thus far

for x in x_values:

y_values.append(pi[x])

pyplot.figure(figsize=(9, 6))

pyplot.plot(x_values, y_values, label="pi(n), prime count")

Finally, we call some built-in pyplot functions to add axes, title, legend, and show the plot in a form that fits the container that we indicated.

def plot_primes(n: int, step: int):

"""

Plots the prime counting function pi(n) as a line graph, sampling every 'step' x-values.

Parameters:

- n (int)

- step (int)

Output:

(nothing, produces plot)

"""

if n < 0 or step < 1:

raise ValueError("Invalid value given.")

# pi[k] = number of primes <= k

pi = prime_count_array(n)

x_values = []

for x in range(2, n + 1, step):

x_values.append(x)

y_values = []

# for a given x, the y-value is pi(x), the number of primes that I have encountered thus far

for x in x_values:

y_values.append(pi[x])

pyplot.figure(figsize=(9, 6))

pyplot.plot(x_values, y_values, label="pi(n), prime count")

pyplot.title("Prime Counting Function pi(n)")

pyplot.xlabel("n")

pyplot.ylabel("pi(n)")

pyplot.legend()

pyplot.tight_layout()

pyplot.show()

We are now ready to run our code, and generate the plot of our prime counting function!

def main():

print("Primes.")

# code omitted for clarity

n = 1000000

step = 100

plot_primes(n, step)

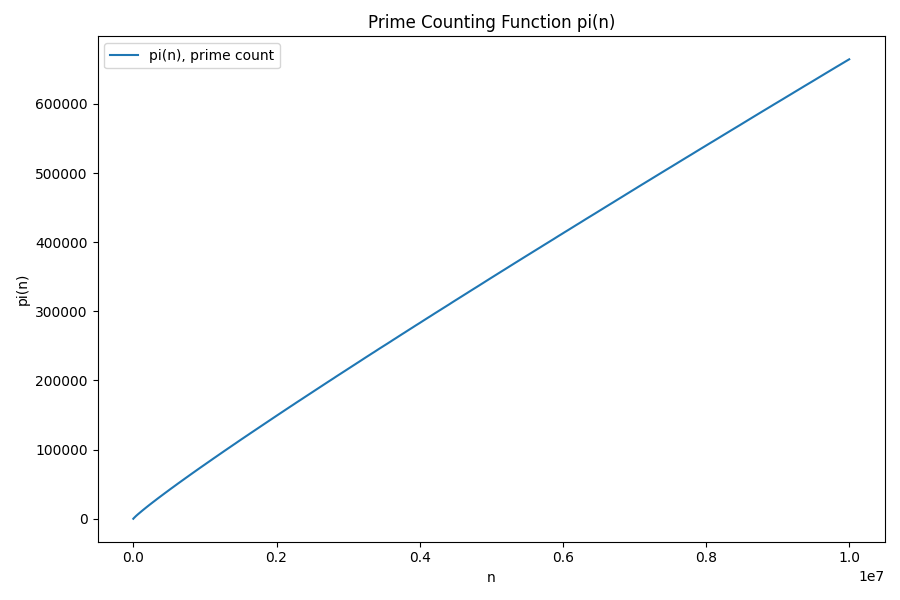

After running our code, we obtain the plot shown in the figure below.

The prime number theorem

The plot of π(n) from the end of the previous section could easily fool us into thinking that the primes grow in a linear fashion. However, a keen eye will notice the very subtle curve present.

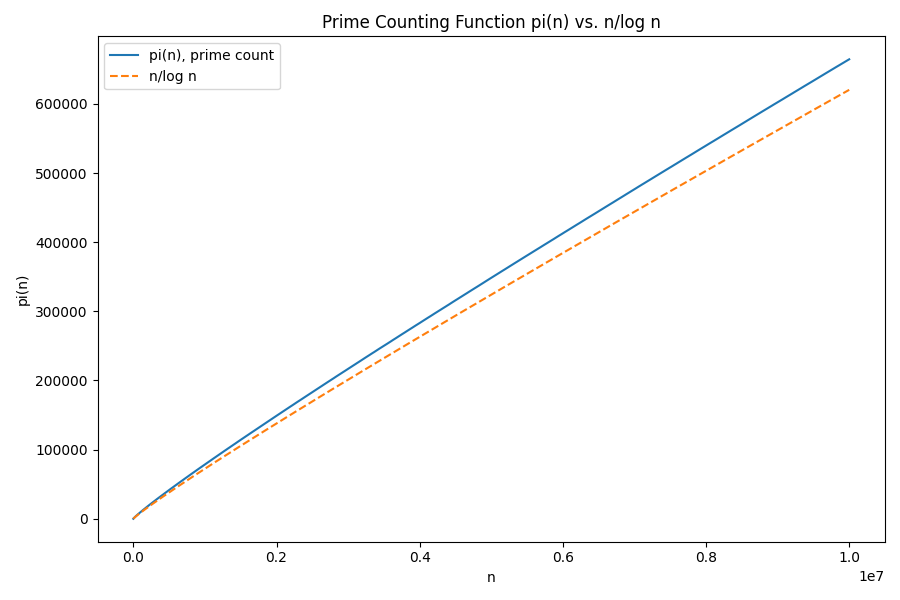

One of the most beautiful discoveries in mathematics is the Prime Number Theorem, proved in 1896, which states that π(n) can be approximated by the function n/log(n) (where log() is the “natural” logarithm with base e = 2.718281828…).

Returning to plot_primes(), we can add the function n/log(n) to our plot by creating a second set of y-values (y_values_approx), which we connect with a dashed curve.

def plot_primes(n: int, step: int):

if n < 0 or step < 1:

raise ValueError("Invalid value given.")

pi = prime_count_array(n)

x_values = []

for x in range(2, n + 1, step):

x_values.append(x)

y_values = []

# for a given x, the y-value is pi(x), the number of primes that I have encountered thus far

for x in x_values:

y_values.append(pi[x])

# approximation curve: n / log(n)

y_values_approx = []

for x in x_values:

y_values_approx.append(x / math.log(x))

pyplot.figure(figsize=(9, 6))

pyplot.plot(x_values, y_values, label="pi(n), prime count")

pyplot.plot(x_values, y_values_approx, linestyle="--", label="n/log n")

pyplot.title("Prime Counting Function pi(n) vs. n/log n")

pyplot.xlabel("n")

pyplot.ylabel("pi(n)")

pyplot.legend()

pyplot.tight_layout()

pyplot.show()

After we run our code with this updated version of plot_primes(), we see that n/log(n) is not a perfect approximation of π(n), but it tracks π(n) remarkably well.

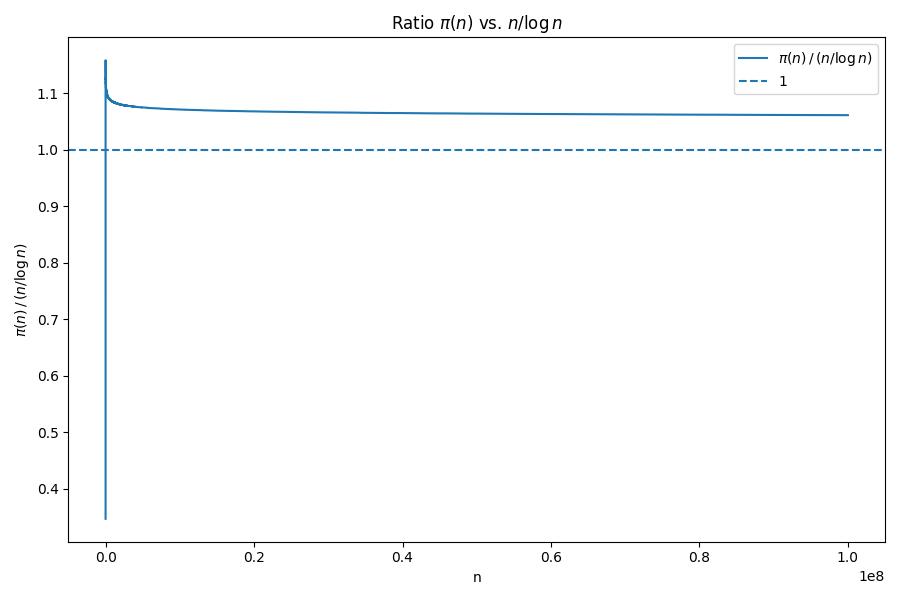

One might look at this plot and imagine that the curves are diverging, which is true. However, we can measure how closely n/log(n) approximates π(n) by considering the ratio between the two functions. In fact, the formal statement of the Prime Number Theorem is that as n grows larger toward infinity, the ratio of π(n) to n/log(n) approaches 1.

Exercise: Use Matplotlib to write a functionplot_ratios()that generates a plot of the ratio of π(n) to n/log(n).

A plot of the ratio of π(n) to n/log(n) is shown in the figure below. It may not appear that this ratio is asymptotically approaching 1, but it is, albeit very slowly! When n is equal to 1024, the ratio is still around 1.02.

Finding big primes

The prime number theorem is one of the great examples of the human spirit establishing something genuinely beautiful. Starting from nothing more than curiosity about numbers, mathematicians uncovered a deep and unexpected law governing the distribution of primes.

Yet the Prime Number Theorem is not just aesthetically pleasing; as we saw when we discussed public key cryptography in the core text, primes are not merely a mathematical curiosity. Modern cryptographic systems rely on the existence of very large prime numbers, often hundreds or thousands of digits long.

Even if our goal is “just” to find large primes, we immediately run into a challenge. Although there are infinitely many prime numbers, they become increasingly rare as numbers grow larger. This phenomenon is exactly what we observed when plotting the prime counting function: the slope of π(n) steadily decreases, drifting toward zero as the primes thin out.

One powerful consequence of the prime number theorem is that it gives us a quantitative way to describe the primes’ sparsity. Roughly speaking, the probability that a randomly chosen large integer near n is prime is well approximated by 1/log(n), where log() once again denotes the natural logarithm.

Consider the largest known prime as of today, which has about 40 million digits. According to the prime number theorem, the probability that a number of that size is prime is on the order of 1 in 100 million.

Even if you focus on a single candidate prime number, establishing that such an enormous number is actually prime is itself a major computational challenge. This task is undertaken by the Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search (GIMPS), a long-running project that distributes the work of a primality testing algorithm across thousands of computers around the world. We will say more about ideas like distributed computing later in the course.

This chapter will end with one final and remarkable twist. The largest known prime is not an arbitrary number; rather, it happens to be equal to 2136,279,841 − 1. Numbers of this form, 2n − 1, are called Mersenne numbers. They are not always prime, but for subtle reasons, they are far more likely to be prime than a “typical” number of comparable size, and we have a faster approach than is_prime() to determine if they are prime. In fact, every largest known prime to date has been a Mersenne prime.

The good news is that if you want to explore Mersenne primes, as well as see how unanswered mathematical questions naturally arise from simple ideas, all while getting more comfort working with Python, we have just the collection of practice exercises for you.

It’s time to practice!

This brings our code alongs for this chapter to a close. Below, we give you the chance to check your work. Once you are finished with this code along, we suggest that you work on this chapter’s fun practice problems that allow you to practice what you have learned throughout this chapter in the context of some unanswered mathematical questions. Or, you can start reading our next chapter on strings and finding hidden messages in DNA.

Check your work from the code along

We provide autograders in the window below (or via a direct link) allowing you to check your work for the following functions:

is_prime()trivial_prime_finder()cross_off_multiples()sieve_of_eratosthenes()list_primes()