Code along video

Although we strongly suggest coding along with us by following the video above, you can find completed code from the code along in our course code repository.

Learning objectives

In this code along, we will give an introduction to graphics in Python using the pygame library. We will use this foundation to draw a snowperson using circles, rectangles, and lines. We will then apply our graphics knowledge to a new project: reading a Game of Life board from a CSV file and drawing it as a pygame.Surface, with improvements to make the visualization more aesthetically appealing. This will set us up to generate animated videos of the Game of Life in the next code along.

Code along summary

Setup

To complete this code along as well as other code alongs relying on graphics in this and following chapters, you will use a popular Python graphics library called pygame, which will help us draw objects and generate images.

First, install pygame by opening a command line terminal and executing the command pip3 install pygame (on macOS/Linux) or pip install pygame (on Windows).

In python/src, create a folder drawing, then create main.py inside it with the following contents. Note that we import the pygame package at the top.

import pygame

def main():

print("Drawing a snowperson.")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Understanding Pygame: our library for drawing

The pygame library allows us to create a graphical window for our programs. We will cover more about object-oriented programming in a future chapter, but for now, think of a pygame window as a rectangular screen with a specified width and height, similar to the screen you are reading this on. The width and height are measured in pixels, where each pixel is a tiny point on the screen that can be colored individually.

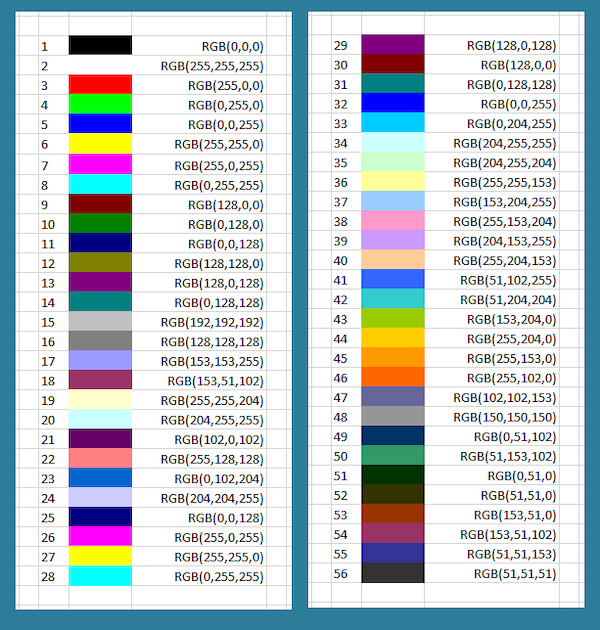

In the RGB color model, every rectangular pixel on a computer screen emits a single color formed as a mixture of differing amounts of the three primary colors of light: red, green, and blue (hence the acronym “RGB”). The intensity of each primary color in a pixel is expressed as an integer between 0 and 255, inclusive, with larger integers corresponding to greater intensities.

A few colors are shown in the figure below along with their RGB equivalents; for example, magenta corresponds to equal parts red and blue. Note that a color like (128, 0, 0) contains only red but appears duskier than (255, 0, 0) because the red in that pixel is less intense.

The functions from pygame that we will need in this and the next code along are listed below. However, a best practice for using Python libraries is to refer to the online API provided here to understand functions and objects in the library: https://www.pygame.org/docs/. We will say more about these functions as they are needed. (Links are provided for specific documentation of each function below for those who are interested.)

pygame.Surface.fill(): Fills the Surface with a solid color. (link)pygame.draw.circle(): draw a circle. (link)pygame.draw.rect(): draw a rectangle. (link)pygame.draw.line(): draw a line. (link)pygame.init(): initialize all imported pygame modules. (link)pygame.Surface(): pygame object for representing images. (link)pygame.image.save(): save an image to file. (link)pygame.quit(): uninitialize all pygame modules. (link)

Creating a blank canvas

In main(), we initialize pygame by calling pygame.init(). Even though we won’t open a window, pygame still needs to set up its internal modules before we can create surfaces or draw anything.

def main():

print("Drawing a snowperson.")

# Initialize pygame but don't open window

pygame.init()

Next, we create a canvas that we can draw on by constructing a new pygame.Surface. We will make our canvas 1000 pixels wide and 2000 pixels tall.

def main():

print("Drawing a snowperson.")

# Initialize pygame but don't open window

pygame.init()

# Create an off-screen surface

width, height = 1000, 2000

surface = pygame.Surface((width, height))

Next, we will define some colors using RGB values. black = (0, 0, 0)white = (255, 255, 255) is full light for all three channels, and red = (255, 0, 0)

def main():

print("Drawing a snowperson.")

pygame.init()

width, height = 1000, 2000

surface = pygame.Surface((width, height))

black = (0, 0, 0)

white = (255, 255, 255)

red = (255, 0, 0)

Next, we paint the entire surface with black by calling surface.fill(black).

def main():

print("Drawing a snowperson.")

pygame.init()

width, height = 1000, 2000

surface = pygame.Surface((width, height))

black = (0, 0, 0)

white = (255, 255, 255)

red = (255, 0, 0)

# Fill canvas with black

surface.fill(black)

Note:surface.fill()is a method (a function that is part of theSurfaceobject) that fills the entire surface with the input color. More information on how to define these functions for objects will be discussed in a future code along.

We can convert our surface to an image by saving it to a PNG so that it can be viewed outside of Python. We call the function pygame.image.save() to produce this PNG, which we will call "snowperson.png".

After we have drawn the face, we call pygame.quit() to shut down all Pygame modules and release all resources. This step is important to prevent memory leaks and save memory and properly close Pygame’s internal systems.

def main():

print("Drawing a snowperson.")

pygame.init()

width, height = 1000, 2000

surface = pygame.Surface((width, height))

black = (0, 0, 0)

white = (255, 255, 255)

red = (255, 0, 0)

surface.fill(black)

pygame.image.save(surface, "snowperson.png")

pygame.quit()

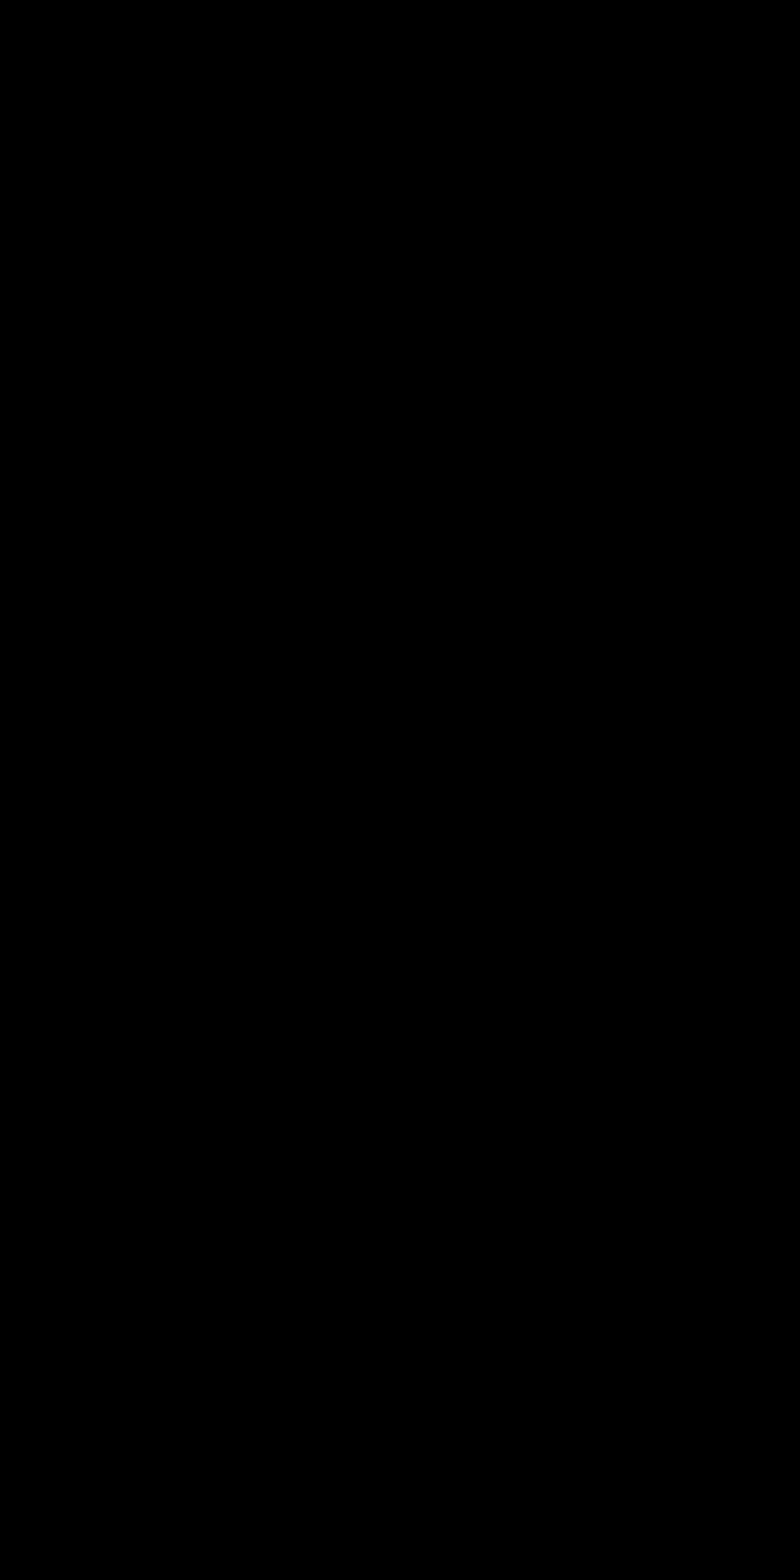

Although we have not yet written code to draw the snowperson, let’s run our code so that we can see what is produced.

STOP: In a new terminal window, navigate into our directory usingcd python/src/drawing. Then run your code by executingpython3 main.py

(macOS/Linux) orpython main.py(Python).

After running your code, you should see the achievement of modern art shown below appear as snowperson.png in your python/src/drawing directory.

The graphics coordinate system

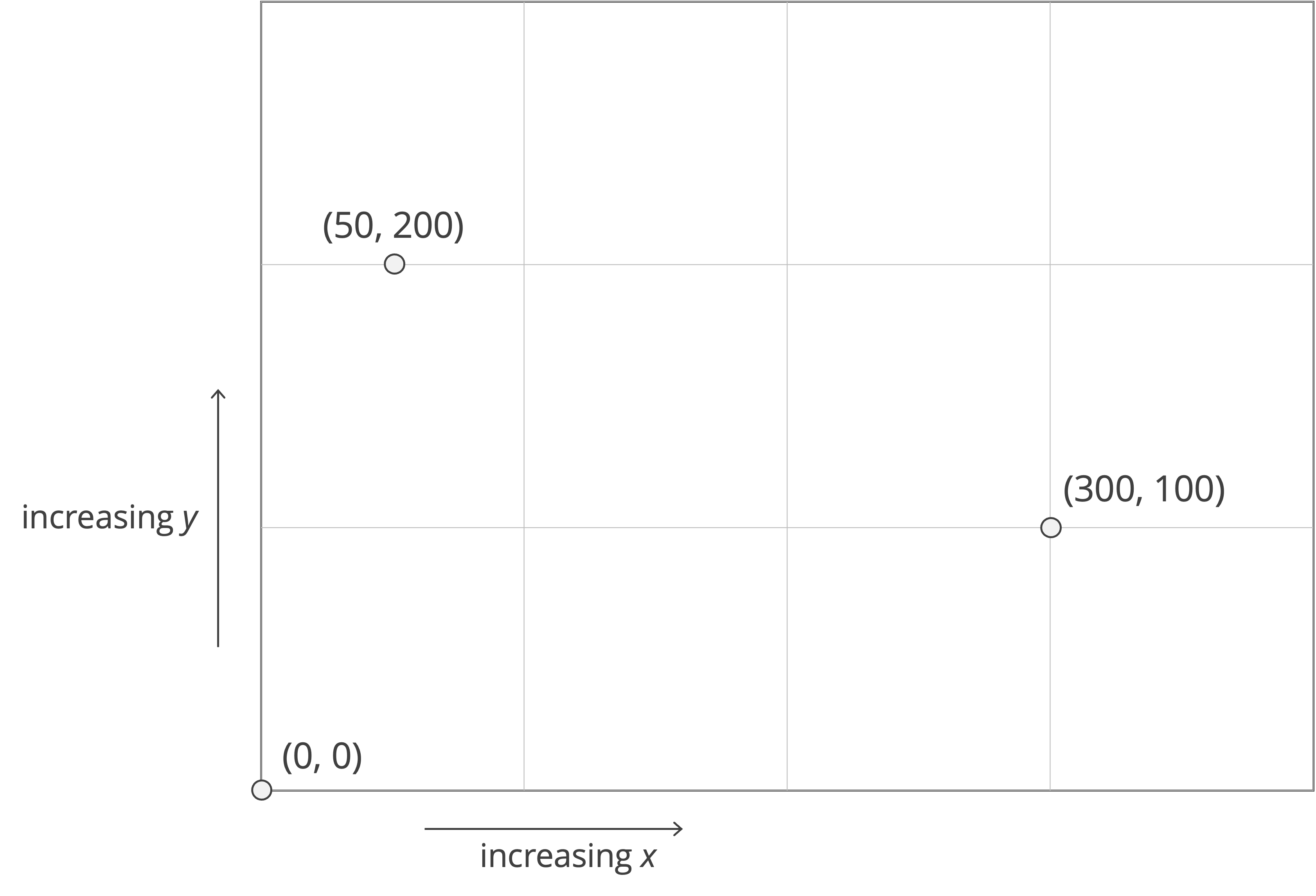

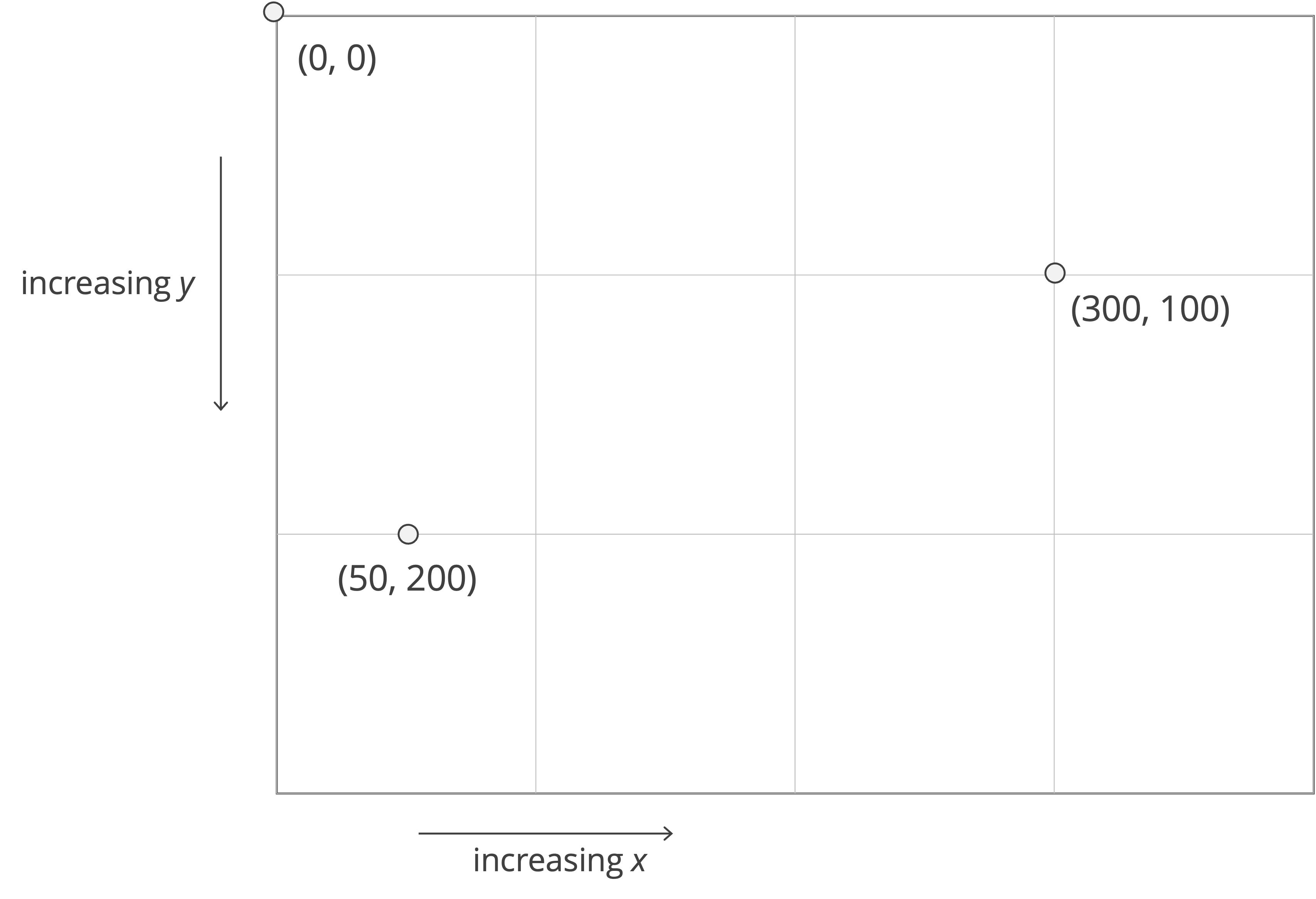

Before adding parts of our snowperson to the drawing, we need to understand the pygame coordinate system. In the Cartesian plane that we are accustomed to working with in mathematics, increasing x-coordinates extend to the right, and increasing y-coordinates extend upward.

However, graphics uses a different standard that dates to the foundation of computing. Many graphics packages (pygame included) use the standard of viewing the top left corner of a window as an “origin”, with increasing x-coordinates extending to the right, and increasing y-coordinates extending downward.

Drawing the snowperson

Rather than placing all our drawing code inside def main(), we will call a function named draw_snowperson(). This function will take our surface as input so that it knows which canvas to draw on, as well as the colors that we plan to use. We update def main() to include the call to draw_snowperson().

def main():

print("Drawing a snowperson.")

pygame.init()

width, height = 1000, 2000

surface = pygame.Surface((width, height))

black = (0, 0, 0)

white = (255, 255, 255)

red = (255, 0, 0)

surface.fill(black)

draw_snowperson(surface, black, white, red)

pygame.image.save(surface, "snowperson.png")

pygame.quit()

We will now implement draw_snowperson(). This function will take the surface as input (our canvas) along with the colors we want to use. Inside draw_snowperson(), we will call three helper functions: draw_head(), draw_middle(), and draw_bottom(). For now, we will comment out the latter two functions so that we can run the code as soon as we finish draw_head().

def draw_snowperson(

surface: pygame.Surface,

black: tuple[int, int, int],

white: tuple[int, int, int],

red: tuple[int, int, int],

) -> None:

draw_head(surface, black, white, red)

# draw_middle(surface, black, white)

# draw_bottom(surface, black, white)

Drawing the head

We will now add a head to surface, which will appear as a white circle near the top of the canvas. To do so, we will call the pygame.draw.circle() function. Remember when your geometry teacher told you that a circle is defined by its center and its radius? We know that you don’t remember it, but it is nevertheless true. We will now use this fact by calling pygame.draw.circle(), which takes four parameters as input:

surfacecolor(255, 0, 0)center(x, y)radius

We want the head to lie in the top part of the rectangle, halfway across from left to right. Because the canvas is 1000 pixels wide, we know that the x-coordinate of the circle’s center should be 500. In order to have the same amount of space on the top, left, and right, let’s make its y-coordinate 500 as well; that is, the circle’s center will be 400 pixels from the top. As for the radius, let’s set it to be 180 pixels. As a result, we will call pygame.draw.circle(surface, white, (500, 400), 180)

def draw_head(

surface: pygame.Surface,

black: tuple[int, int, int],

white: tuple[int, int, int],

red: tuple[int, int, int],

) -> None:

pygame.draw.circle(surface, white, (500, 400), 180)

When we run our code again, we obtain the head below as snowperson.png.

Adding facial features to the head

Now that we have a head, it is time to give our snowperson a personality (or at least some facial features). We will add eyes, a nose, eyebrows, and a mouth.

We will start with a nose, which we will draw as a small black circle slightly below the eyes. The nose’s x-coordinate stays at 500 (we respect symmetry), and we’ll place it at y-coordinate 410. We will give it radius 10 pixels.

def draw_head(

surface: pygame.Surface,

black: tuple[int, int, int],

white: tuple[int, int, int],

red: tuple[int, int, int],

) -> None:

pygame.draw.circle(surface, white, (500, 400), 180)

# add nose (black circle)

pygame.draw.circle(surface, black, (500, 410), 10)

Next we add two circular black eyes. We will place them slightly above the center of the head. Since our head is centered at (500, 400), let’s put the eyes at y-coordinate 360. We will move them 60 pixels left and right of the center line, so their x-coordinates will be 440 and 560. We will set their radii to 15 pixels so that our snowperson can actually see.

def draw_head(

surface: pygame.Surface,

black: tuple[int, int, int],

white: tuple[int, int, int],

red: tuple[int, int, int],

) -> None:

pygame.draw.circle(surface, white, (500, 400), 180)

# add nose (black circle)

pygame.draw.circle(surface, black, (500, 410), 10)

# add eyes (black circles)

pygame.draw.circle(surface, black, (440, 360), 15)

pygame.draw.circle(surface, black, (560, 360), 15)

Running our code produces the unsettling stare shown below.

Now for a mouth. We will make it a red rectangle so that we can use pygame.draw.rect(). This function takes (x, y, width, height)(x, y)

def draw_head(

surface: pygame.Surface,

black: tuple[int, int, int],

white: tuple[int, int, int],

red: tuple[int, int, int],

) -> None:

pygame.draw.circle(surface, white, (500, 400), 180)

# add nose (black circle)

pygame.draw.circle(surface, black, (500, 410), 10)

# add eyes (black circles)

pygame.draw.circle(surface, black, (440, 360), 15)

pygame.draw.circle(surface, black, (560, 360), 15)

# add mouth (red rectangle)

pygame.draw.rect(surface, red, (430, 450, 140, 20))

Finally, we will add eyebrows using pygame.draw.line()

def draw_head(

surface: pygame.Surface,

black: tuple[int, int, int],

white: tuple[int, int, int],

red: tuple[int, int, int],

) -> None:

pygame.draw.circle(surface, white, (500, 400), 180)

pygame.draw.circle(surface, black, (440, 360), 15)

pygame.draw.circle(surface, black, (560, 360), 15)

pygame.draw.circle(surface, black, (500, 410), 10)

pygame.draw.rect(surface, red, (430, 450, 140, 20))

# add eyebrows (thick black lines)

pygame.draw.line(surface, black, (420, 310), (470, 340), 10)

pygame.draw.line(surface, black, (580, 310), (530, 340), 10)

Running the program now produces the completed head below.

Drawing the middle

Next, we will draw the middle circle of the snowperson below the head. In addition to another larger circle, we will add two buttons as small black circles.

def draw_middle(

surface: pygame.Surface,

black: tuple[int, int, int],

white: tuple[int, int, int],

) -> None:

pygame.draw.circle(surface, white, (500, 800), 260)

pygame.draw.circle(surface, black, (500, 760), 12)

pygame.draw.circle(surface, black, (500, 860), 12)

Drawing the bottom

Finally, we draw the bottom circle of the snowperson and add three buttons down the center.

def draw_bottom(

surface: pygame.Surface,

black: tuple[int, int, int],

white: tuple[int, int, int],

) -> None:

pygame.draw.circle(surface, white, (500, 1300), 360)

pygame.draw.circle(surface, black, (500, 1200), 12)

pygame.draw.circle(surface, black, (500, 1320), 12)

pygame.draw.circle(surface, black, (500, 1440), 12)

Full program

Putting everything together, we uncomment draw_middle() and draw_bottom() in draw_snowperson() our complete main.py is shown below.

def main():

print("Drawing a snowperson.")

pygame.init()

width, height = 1000, 2000

surface = pygame.Surface((width, height))

black = (0, 0, 0)

white = (255, 255, 255)

red = (255, 0, 0)

surface.fill(black)

draw_snowperson(surface, black, white, red)

pygame.image.save(surface, "fun.png")

pygame.quit()

When we run our code, we obtain the final snowperson below.

Drawing a Game of Life Board

Setting up the Game of Life starter code

To complete the rest of this code along and the next code along on implementing the Game of Life, we will need starter code.

We provide this starter code as a single download game_of_life.zip. Download this code here, and then expand the folder. Move the resulting game_of_life directory into your python/src source code directory.

The game_of_life directory has the following structure:

boards: a directory containing.csvfiles that represent different initial Game of Life board states (more on this directory shortly).output: an initially empty directory that will contain images and mp4 videos that we draw.datatypes.py: a file that will contain type declarations (more to come shortly).functions.py: a file that will contain functions that we will write in the next code along for implementing the Game of Life.custom_io.py: a file that will contain code for reading in a Game of Life board from file.drawing.py: a file that will contain code for drawing a Game of Life board to a file.main.py: a file that will containdef main(), where we will call functions to read in Game of Life boards and then draw them.

Declaring a GameBoard type

We already know that we conceptualize a Game of Life board as a two-dimensional list of boolean variables, in which True denotes that a cell is alive, and False denotes that it is dead. When implementing the Game of Life in the next code along, we will need to store such a board for each of a number of generations. The result of the simulation will therefore have type list[list[list[bool]]], which is a three-dimensional list of boolean variables.

Do not worry if you find this tricky to conceptualize. Rather, think about the end result of the Game of Life as providing us with a list of game boards, where each game board is a two-dimensional list of boolean variables.

Fortunately, Python provides a way to implement this abstraction. In datatypes.py, we will add the following type declaration that establishes a new GameBoard type as an alias; that is, we can use GameBoard wherever we might otherwise use a two-dimensional list of booleans.

# GameBoard is a two-dimensional list of boolean variables # representing a single generation of a Game of Life board. GameBoard = list[list[bool]]

Once we have added this code, we can use GameBoard in place of list[list[bool]] whenever we are referring to a Game of Life board. As a result, the Game of Life simulation that we will complete in the next code along will produce a variable of type list[GameBoard], a list of GameBoard objects.

We will say much more about the transition toward abstracting variables as objects in our next chapter. For now, let’s learn how to read in a GameBoard from file and then draw it.

Reading in a Game of Life board from file

In the previous code along, we entered the cells of a Game of Life board manually, an approach that will not work for larger boards. Instead, let’s write a function to read a Game of Life board from file. Note that the boards directory contains three comma-separated files.

dinnerTable.csv: the period-12 dinner table oscillator that we encountered in the main text.rPentomino.csv: the five-cell R Pentomino pattern that produces surprisingly complex behavior, including the production of six gliders.gosperGun.csv: the “Gosper gun” that manufactures gliders at a constant rate.

We reproduce the animations of these three initial patterns below according to the above order.

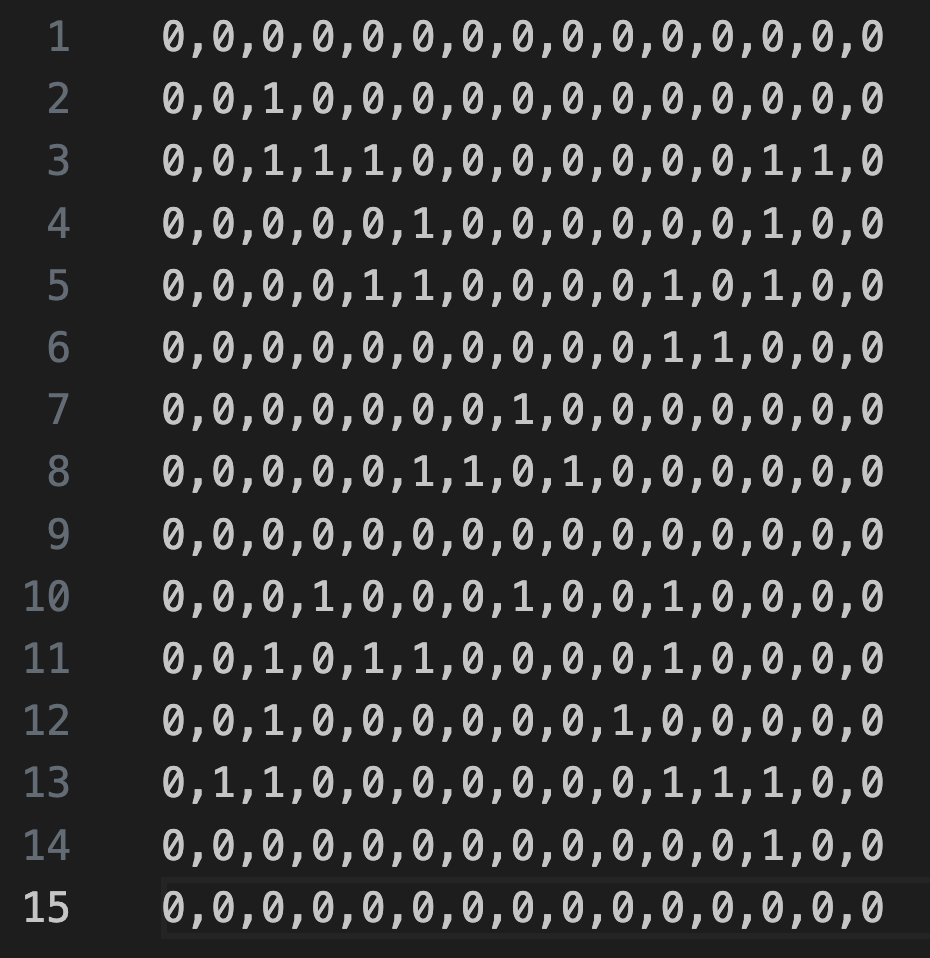

Open and examine one of the files in boards. Each row of the file contains a single line of comma-separated integers representing a row of the board, with alive cells represented by 1 and dead cells represented by 0.

We will write a function read_board_from_file() in custom_io.py that takes as input a string filename, reads in a file from the location specified in filename, and then returns a GameBoard representing the automaton specified in the file according to the above mentioned format.

In custom_io.py, we will introduce and use the following functions and expressions, which we will cover in more detail shortly.

open(filename, 'r'): Opens the file in read mode, giving back a file object.with ... as f: Ensures the file is closed automatically after use (safe practice).f.read(): Reads the entire contents of the file into a single string..strip(): Removes any extra spaces or newlines at the start and end..splitlines(): Splits the file into separate lines, making a list of strings (one string per row of the board).

At the top of the file, you should see:

from datatypes import GameBoard

This allows us to access the GameBoard alias that we defined in datatypes in datatypes.py.

The function read_board_from_file() reads in a CSV file like the ones we have, which represent a Game of Life board. It will return the corresponding GameBoard board.

def read_board_from_file(filename: str) -> GameBoard:

"""

Reads a CSV file representing a Game of Life board.

Each element in the file is either "1" (alive) or "0" (dead).

The file is parsed into a GameBoard data structure.

Parameters:

- filename (str): The name of the CSV file to read.

Returns:

- GameBoard: A board where True represents alive and False represents dead.

"""

if not isinstance(filename, str) or len(filename) == 0:

raise ValueError("filename must be a non-empty string.")

# to be implemented...

Inside our function, we need to open the file so we can read its contents. The function call open(filename, 'r') as f opens the file having name filename in read mode ('r'), and it returns a file object called f. We place the word with before the call to open(), which means that we will indent the code immediately following the open() statement as a block. When the block is complete, Python automatically closes the file, even if something goes wrong, which is considered good practice because it prevents resource leaks.

def read_board_from_file(filename: str) -> GameBoard:

"""

Reads a CSV file representing a Game of Life board.

Each element in the file is either "1" (alive) or "0" (dead).

The file is parsed into a GameBoard data structure.

Parameters:

- filename (str): The name of the CSV file to read.

Returns:

- GameBoard: A board where True represents alive and False represents dead.

"""

if not isinstance(filename, str) or len(filename) == 0:

raise ValueError("filename must be a non-empty string.")

with open(filename, 'r') as f:

# to be implemented...

Next, we call the function f.read() to store the entire contents of the file into a string, which we will call giant_string.

def read_board_from_file(filename: str) -> GameBoard:

"""

Reads a CSV file representing a Game of Life board.

Each element in the file is either "1" (alive) or "0" (dead).

The file is parsed into a GameBoard data structure.

Parameters:

- filename (str): The name of the CSV file to read.

Returns:

- GameBoard: A board where True represents alive and False represents dead.

"""

if not isinstance(filename, str) or len(filename) == 0:

raise ValueError("filename must be a non-empty string.")

with open(filename, 'r') as f:

giant_string = f.read()

# to be implemented...

This concludes the with block, which will close the file, since we have the file’s contents stored in giant_string.

We then call the function giant_string.strip() to return a new string with any leading or trailing white space removed and store it in the variable trimmed_giant_string.

Then we apply the function trimmed_giant_string.splitlines() to split trimmed_giant_string into a list of strings lines, where each element of lines is a string corresponding to a single line of the file.

def read_board_from_file(filename: str) -> GameBoard:

"""

Reads a CSV file representing a Game of Life board.

Each element in the file is either "1" (alive) or "0" (dead).

The file is parsed into a GameBoard data structure.

Parameters:

- filename (str): The name of the CSV file to read.

Returns:

- GameBoard: A board where True represents alive and False represents dead.

"""

if not isinstance(filename, str) or len(filename) == 0:

raise ValueError("filename must be a non-empty string.")

with open(filename, 'r') as f:

giant_string = f.read()

# trim any space at the start or end of file

trimmed_giant_string = giant_string.strip()

# split the long string into multiple strings, one for each line

lines = trimmed_giant_string.splitlines()

# to be implemented...

We know that each line in the file corresponds to a single row in our desired GameBoard, and so we can go ahead and declare this GameBoard, which we will initialize as board (which is an empty list). To do so, we use the declaration board: GameBoard = [].

We will also add a return board statement to the bottom of the function, leaving the middle of the function remaining, where we will read through lines and set the elements of board.

def read_board_from_file(filename: str) -> GameBoard:

"""

Reads a CSV file representing a Game of Life board.

Each element in the file is either "1" (alive) or "0" (dead).

The file is parsed into a GameBoard data structure.

Parameters:

- filename (str): The name of the CSV file to read.

Returns:

- GameBoard: A board where True represents alive and False represents dead.

"""

if not isinstance(filename, str) or len(filename) == 0:

raise ValueError("filename must be a non-empty string.")

with open(filename, 'r') as f:

giant_string = f.read()

# trim any space at the start or end of file

trimmed_giant_string = giant_string.strip()

# split the long string into multiple strings, one for each line

lines = trimmed_giant_string.splitlines()

board: GameBoard = [] # declare an empty GameBoard

# fill in...

return board

Next, we loop over the elements of lines, each of which is a list current_line consisting of 0 and 1 values separated by commas. We split current_line by commas using .split(','), which produces a list of strings, where each string is either "0" or "1", representing a dead or alive cell in the Game of Life, respectively.

def read_board_from_file(filename: str) -> GameBoard:

"""

Reads a CSV file representing a Game of Life board.

Each element in the file is either "1" (alive) or "0" (dead).

The file is parsed into a GameBoard data structure.

Parameters:

- filename (str): The name of the CSV file to read.

Returns:

- GameBoard: A board where True represents alive and False represents dead.

"""

if not isinstance(filename, str) or len(filename) == 0:

raise ValueError("filename must be a non-empty string.")

with open(filename, 'r') as f:

# first, convert the whole file to a string

giant_string = f.read()

# trim any space at the start or end of file

trimmed_giant_string = giant_string.strip()

# split the long string into multiple strings, one for each line

lines = trimmed_giant_string.splitlines()

board = []

# we will iterate over each line, parse the data in each line, and build the board

for current_line in lines:

line_elements = current_line.split(',')

# line_elements contains a list of strings, one for each element in the row, i.e., a bunch of "0" and "1" strings

# to fill in

return board

In the spirit of modularity and avoiding unnecessary nested loops, we will set the values of the current row of board by passing line_elements into a subroutine, which we call set_row_values(). This function takes as input a string representing a line of a comma-separated Game of Life, and it returns a list of boolean values corresponding to parsing the line, where "1" is parsed as True and "0" is parsed as False.

def read_board_from_file(filename: str) -> GameBoard:

"""

Reads a CSV file representing a Game of Life board.

Each element in the file is either "1" (alive) or "0" (dead).

The file is parsed into a GameBoard data structure.

Parameters:

- filename (str): The name of the CSV file to read.

Returns:

- GameBoard: A board where True represents alive and False represents dead.

"""

if not isinstance(filename, str) or len(filename) == 0:

raise ValueError("filename must be a non-empty string.")

with open(filename, 'r') as f:

# first, convert the whole file to a string

giant_string = f.read()

# trim any space at the start or end of file

trimmed_giant_string = giant_string.strip()

# split the long string into multiple strings, one for each line

lines = trimmed_giant_string.splitlines()

board = []

# we will iterate over each line, parse the data in each line, and build the board

for current_line in lines:

line_elements = current_line.split(',')

# line_elements contains a list of strings, one for each element in the row, i.e., a bunch of "0" and "1" strings

new_row = set_row_values(line_elements)

board.append(new_row)

return board

Finally, after we read in the board, let’s have a quick sanity check asserting that it is rectangular. We will dive deeper into the assert_rectangular() function in a moment!

def read_board_from_file(filename: str) -> GameBoard:

"""

Reads a CSV file representing a Game of Life board.

Each element in the file is either "1" (alive) or "0" (dead).

The file is parsed into a GameBoard data structure.

Parameters:

- filename (str): The name of the CSV file to read.

Returns:

- GameBoard: A board where True represents alive and False represents dead.

"""

if not isinstance(filename, str) or len(filename) == 0:

raise ValueError("filename must be a non-empty string.")

with open(filename, 'r') as f:

# first, convert the whole file to a string

giant_string = f.read()

# trim any space at the start or end of file

trimmed_giant_string = giant_string.strip()

# split the long string into multiple strings, one for each line

lines = trimmed_giant_string.splitlines()

board = []

# we will iterate over each line, parse the data in each line, and build the board

for current_line in lines:

line_elements = current_line.split(',')

# line_elements contains a list of strings, one for each element in the row, i.e., a bunch of "0" and "1" strings

new_row = set_row_values(line_elements)

board.append(new_row)

# sanity check: is my board rectangular?

assert_rectangular(board)

return board

We now write set_row_values(), which first makes a list current_row of boolean variables having length equal to the number of elements in line_elements. It then loops over line_elements, appending the corresponding value of current_row equal to False if the corresponding value of line_elements is "0", and True if the corresponding value of line_elements is "1".

def set_row_values(line_elements: list[str]) -> list[bool]:

"""

Converts a list of "0"/"1" strings into a list of booleans.

Parameters:

- line_elements (list[str]): A list of strings containing "0" or "1".

Returns:

- list[bool]: A row where "0" is False and "1" is True.

"""

if not isinstance(line_elements, list) or len(line_elements) == 0:

raise ValueError("line_elements must be a non-empty list of '0'/'1' strings.")

current_row = []

# range over elements of lineElement and convert them to booleans

for val in line_elements:

if val == '0':

current_row.append(False)

elif val == '1':

current_row.append(True)

else:

raise ValueError("Error: invalid entry in board file.")

return current_row

Drawing a Game of Life board

In drawing.py, let’s write a function draw_game_board() that takes as input a GameBoard object board in addition to an integer cell_width. This function will create a pygame.Surface object named surface, a virtual canvas in which each cell is assigned a square that is cell_width pixels wide and tall. The function then returns surface, which can later be rendered to display the board image.

At the top of drawing.py, we will import pygame and the GameBoard datatype that we created. We will also import two functions count_rows() and count_cols() that we will write in functions.py shortly for determining the dimensions of a board.

import pygame # for drawing on a surface object from datatypes import GameBoard # our GameBoard datatype from functions import count_rows, count_cols

Next, we will set the height of the surface (in pixels) equal to the number of rows in board times cell_width, and the width of the canvas equal to the number of columns in board times cell_width, using the count_rows() and count_cols() subroutines.

def draw_game_board(board: GameBoard, cell_width: int) -> pygame.Surface:

"""

Draw a single GameBoard as a pygame.Surface.

Args:

board (GameBoard): A 2D list of booleans representing the game state

(True = alive cell, False = dead cell).

cell_width (int): Pixel width of each cell in the drawing.

Returns:

pygame.Surface: A surface with the GameBoard visually rendered,

where alive cells are drawn as white squares and dead cells remain background-colored.

"""

if not isinstance(cell_width, int) or cell_width <= 0:

raise ValueError("cell_width must be a positive integer.")

if not isinstance(board, list) or len(board) == 0:

raise ValueError("board must be a non-empty 2D list.")

width = count_cols(board) * cell_width

height = count_rows(board) * cell_width

# to fill in

Then, we will call pygame.Surface((width, height)) from the pygame package to create a new pygame.Surface object called surface that is width pixels wide and height pixels tall.

At the end of our function, we will eventually return the pygame.Surface object associated with our canvas.

def draw_game_board(board: GameBoard, cell_width: int) -> pygame.Surface:

"""

Draw a single GameBoard as a pygame.Surface.

Args:

board (GameBoard): A 2D list of booleans representing the game state

(True = alive cell, False = dead cell).

cell_width (int): Pixel width of each cell in the drawing.

Returns:

pygame.Surface: A surface with the GameBoard visually rendered,

where alive cells are drawn as white squares and dead cells remain background-colored.

"""

if not isinstance(cell_width, int) or cell_width <= 0:

raise ValueError("cell_width must be a positive integer.")

if not isinstance(board, list) or len(board) == 0:

raise ValueError("board must be a non-empty 2D list.")

width = count_cols(board) * cell_width

height = count_rows(board) * cell_width

# create a drawing surface

surface = pygame.Surface((width, height))

# to fill in

return surface

Next, we will declare two color variables, one for a dark gray color (RGB: (60, 60, 60)) and one for white (RGB: (255, 255, 255)). After doing so, we will call surface.fill() to fill the entire canvas with dark gray.

def draw_game_board(board: GameBoard, cell_width: int) -> pygame.Surface:

"""

Draw a single GameBoard as a pygame.Surface.

Args:

board (GameBoard): A 2D list of booleans representing the game state

(True = alive cell, False = dead cell).

cell_width (int): Pixel width of each cell in the drawing.

Returns:

pygame.Surface: A surface with the GameBoard visually rendered,

where alive cells are drawn as white squares and dead cells remain background-colored.

"""

if not isinstance(cell_width, int) or cell_width <= 0:

raise ValueError("cell_width must be a positive integer.")

if not isinstance(board, list) or len(board) == 0:

raise ValueError("board must be a non-empty 2D list.")

width = count_cols(board) * cell_width

height = count_rows(board) * cell_width

# create a drawing surface

surface = pygame.Surface((width, height))

# declare some color variables

dark_gray = (60, 60, 60)

white = (255, 255, 255)

# set the background color of the board to gray

surface.fill(dark_gray)

# to fill in

return surface

We are now ready to range over every cell in board and color a given cell white if it is alive. We don’t need to take any action if the cell is dead, since the color of dead cells will be the same as the background color.

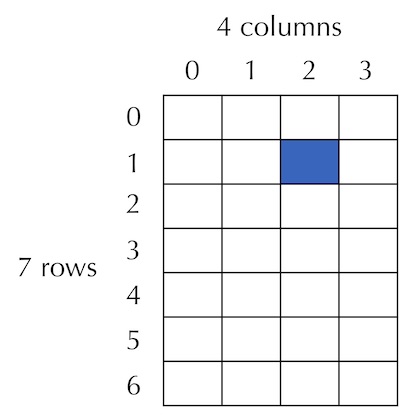

Although we are ardent followers of modularity, in this particular case, we don’t mind using a nested for loop to range over board is in order, since our code will be short. After ranging i over the rows of board and j over the columns of board, we will draw a rectangle at the position on the canvas corresponding to board[i][j]. The question is precisely where on the canvas we should draw this rectangle.

def draw_game_board(board: GameBoard, cell_width: int) -> pygame.Surface:

"""

Draw a single GameBoard as a pygame.Surface.

Args:

board (GameBoard): A 2D list of booleans representing the game state

(True = alive cell, False = dead cell).

cell_width (int): Pixel width of each cell in the drawing.

Returns:

pygame.Surface: A surface with the GameBoard visually rendered,

where alive cells are drawn as white squares and dead cells remain background-colored.

"""

if not isinstance(cell_width, int) or cell_width <= 0:

raise ValueError("cell_width must be a positive integer.")

if not isinstance(board, list) or len(board) == 0:

raise ValueError("board must be a non-empty 2D list.")

width = count_cols(board) * cell_width

height = count_rows(board) * cell_width

# create a drawing surface

surface = pygame.Surface((width, height))

# declare some color variables

dark_gray = (60, 60, 60)

white = (255, 255, 255)

# set the background color of the board to gray

surface.fill(dark_gray)

# fill in the colored squares

for i in range(len(board)):

for j in range(len(board[0])):

# only draw the cell if it's alive, since it would equal background color

if board[i][j]:

# draw the cell at the appropriate location. But where?

return surface

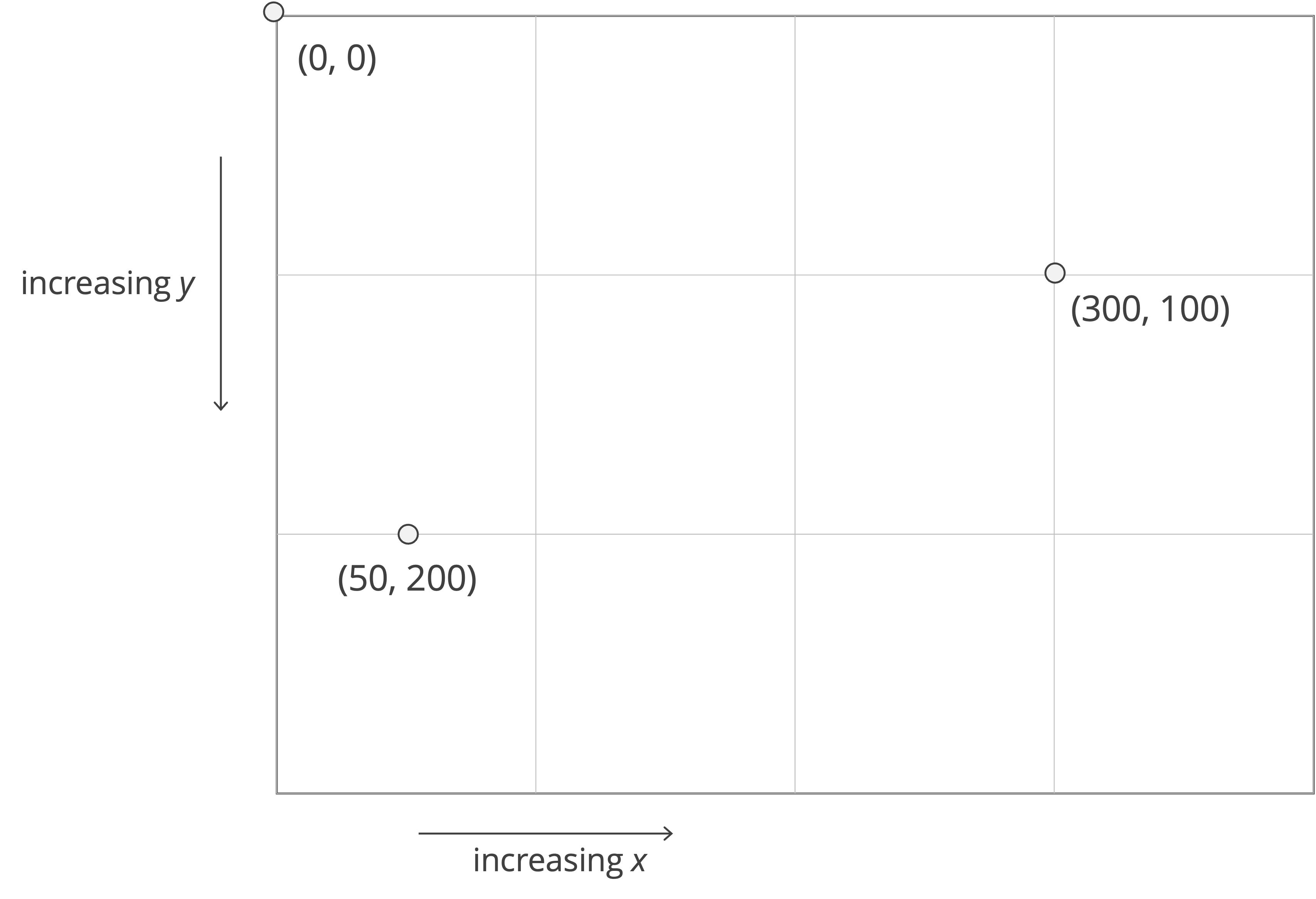

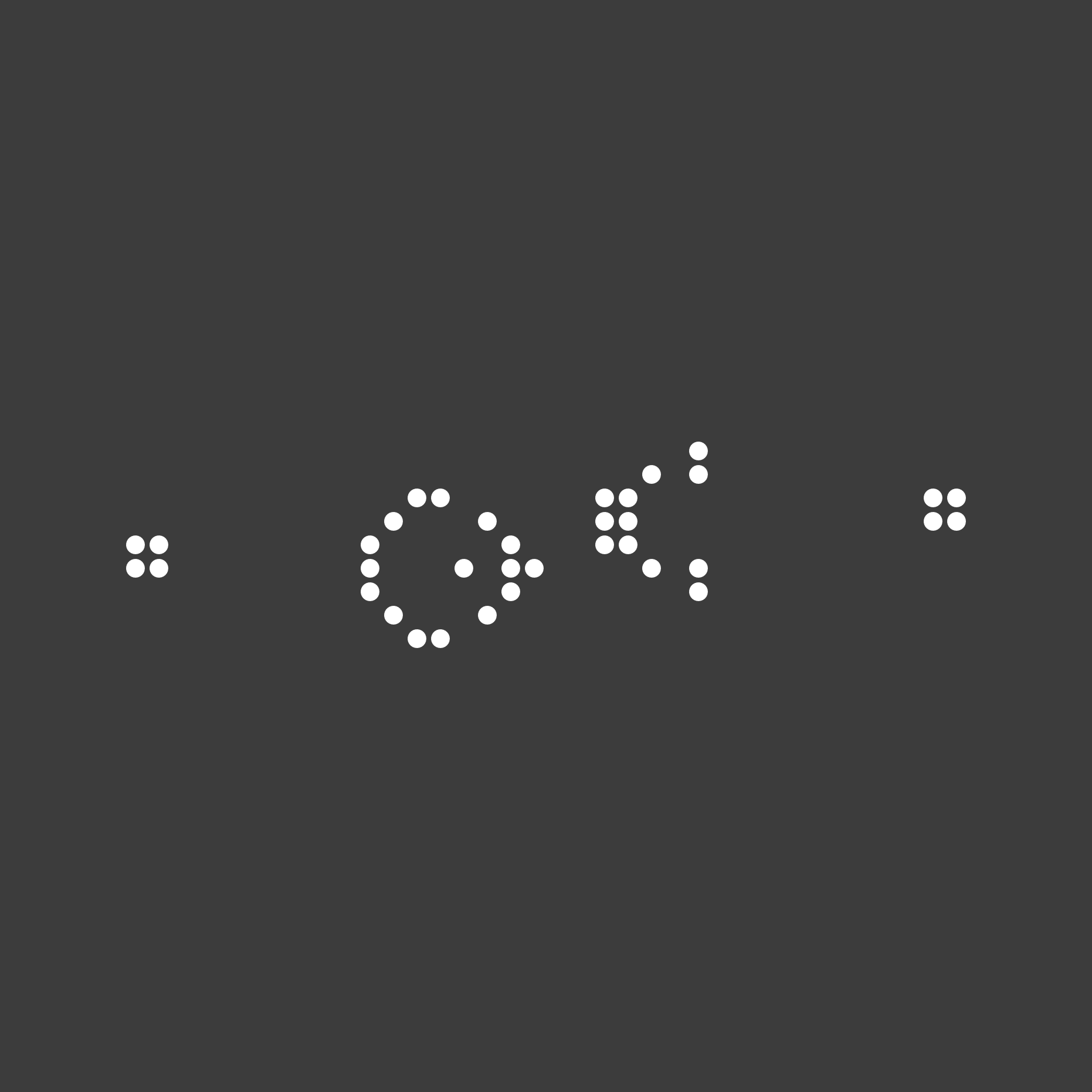

Let us recall for a moment how we conceptualize arrays. As shown in the figure below on the left, the rows of an array extend downward from the top left, and the columns of the array extend rightward from the top left. This is similar to the standard computer graphics approach (reproduced below on the right), except that the rows increase in proportion to y-coordinates, and the columns increase in proportion to x-coordinates. Therefore, although we are tempted to think that an element a[r][c] of an array will be drawn at a position (x, y), where x depends on r and y depends on c, the opposite is true: x depends on c, and y depends on r.

We now know that to draw the rectangle associated with board[i][j], the minimum x-value will be the product of j, the column index, and cell_width; the minimum y-value will be the product of i, the row index, and cell_width. We define the rectangle’s left and top coordinates to be x and y, and the added width and height are both cell_width because we are drawing a square. We are now ready to finish draw_game_board().

def draw_game_board(board: GameBoard, cell_width: int) -> pygame.Surface:

"""

Draw a single GameBoard as a pygame.Surface.

Args:

board (GameBoard): A 2D list of booleans representing the game state

(True = alive cell, False = dead cell).

cell_width (int): Pixel width of each cell in the drawing.

Returns:

pygame.Surface: A surface with the GameBoard visually rendered,

where alive cells are drawn as white squares and dead cells remain background-colored.

"""

if not isinstance(cell_width, int) or cell_width <= 0:

raise ValueError("cell_width must be a positive integer.")

if not isinstance(board, list) or len(board) == 0:

raise ValueError("board must be a non-empty 2D list.")

width = count_cols(board) * cell_width

height = count_rows(board) * cell_width

# create a drawing surface

surface = pygame.Surface((width, height))

# declare some color variables

dark_gray = (60, 60, 60)

white = (255, 255, 255)

# set the background color of the board to gray

surface.fill(dark_gray)

# fill in the alive squares

for i in range(len(board)):

for j in range(len(board[0])):

if board[i][j]:

x = j * cell_width

y = i * cell_width

pygame.draw.rect(surface, white, (int(x), int(y), cell_width, cell_width))

# return the surface with the board drawn on it

return surface

Two seemingly simple subroutines, and an introduction to assertion functions

We now just need to write the subroutines count_rows() and count_cols(), which we will place in functions.py because they are general purpose functions not specific to drawing. Then, we will be ready to write some code in def main() to read in a Game of Life board using read_board_from_file() and draw it using draw_game_board().

We can count the number of rows in board by accessing len(board), and we can count the number of columns in board by accessing the length of the first row, len(board[0]). In count_cols(), we make sure to check that board doesn’t have zero rows, so that when we access board[0], we know that it exists.

STOP: What issue do you see that might arise with these two functions?

def count_rows(board: GameBoard) -> int:

"""

Count the number of rows in a GameBoard.

Args:

board (GameBoard): A 2D list of booleans representing the game state.

Returns:

int: Number of rows in the board.

"""

if not isinstance(board, list):

raise ValueError("board must be a list.")

return len(board)

def count_cols(board: GameBoard) -> int:

"""

Count the number of columns in a GameBoard.

Args:

board (GameBoard): A 2D list of booleans representing the game state.

Returns:

int: Number of columns in the board.

Raises:

ValueError: If the board is not rectangular.

"""

if not isinstance(board, list) or len(board) == 0:

raise ValueError("board must be a non-empty 2D list.")

if len(board) == 0:

raise ValueError("Error: no rows in GameBoard.")

return len(board[0])

Although count_rows() always correctly the number of rows in a two-dimensional list, recall from our creation of a triangular list in the previous code along that a two-dimensional list does not necessarily have the same number of elements in each row.

We could make our code more robust in one of two ways. First, we could return the maximum length of any row of board. However, the strategy that we will take is to revise count_cols() so that it only returns a value if board is rectangular. To do so, at the beginning of count_cols(), we will call a subroutine assert_rectangular(), which takes board as input. This assertion function does not return anything, but it raises an exception if board has no rows, or if when we range over the rows of board, any row has length that is not equal to the length of the initial row of board.

def count_cols(board: GameBoard) -> int:

"""

Count the number of columns in a GameBoard.

Args:

board (GameBoard): A 2D list of booleans representing the game state.

Returns:

int: Number of columns in the board.

Raises:

ValueError: If the board is not rectangular.

"""

if not isinstance(board, list) or len(board) == 0:

raise ValueError("board must be a non-empty 2D list.")

assert_rectangular(board)

return len(board[0])

def assert_rectangular(board: GameBoard) -> None:

"""

Ensure that a GameBoard is rectangular.

Args:

board (GameBoard): A 2D list of booleans representing the game state.

Raises:

ValueError: If the board has no rows or if its rows are not of equal length.

"""

if not isinstance(board, list) or len(board) == 0:

raise ValueError("board must be a non-empty 2D list.")

# range over rows and ensure that every row has same length (i.e., every row has the length of the first row).

first_row_length = len(board[0])

for row in range(1, len(board)):

if len(board[row]) != first_row_length:

raise ValueError("Error: GameBoard is not rectangular.")

Note: Halting the program is a strict decision to make for a non-rectangular board. In practice, we might make different design choices, such as providing a message to the user.

Running our code, and improving our automaton visualization

In main.py, we will add the following import statements. In the next code along, we will add some more import statements that will allow us to create a video out of pygame surfaces.

import pygame import numpy from custom_io import read_board_from_file from drawing import draw_game_board # returns a pygame.Surface # in the next codealong we will add more imports

In def main(), we will first read a board from file. Let’s read the simplest board, the R pentomino, which is stored in boards/rPentomino.csv. We will then set our cell_width parameter to 20 pixels, and call draw_game_board() on rPentomino and cell_width.

At the top, we will initialize all pygame modules using pygame.init(), and below the rest of the code we will shut down all the modules with pygame.quit().

def main():

"""Read a board CSV, render it, and save to PNG."""

pygame.init()

# read the board from file

r_pentomino = read_board_from_file("boards/rPentomino.csv")

cell_width = 20

surface = draw_game_board(r_pentomino, cell_width)

pygame.quit()

The reference to the pygame.Surface object that we generated is stored in a variable called surface, which we want to write to a file to view. First, we declare a string filename, which we will set to be equal to "output/rPentomino.png", so that our image will be written into the output directory.

We then call pygame.image.save(surface, filename), which ensures that the image is saved to that file.

def main():

pygame.init()

# read the board from file

r_pentomino = read_board_from_file("boards/rPentomino.csv")

cell_width = 20

surface = draw_game_board(r_pentomino, cell_width)

# Save surface as PNG

filename = "output/rPentomino.png"

pygame.image.save(surface, filename)

pygame.quit()

STOP: In a new terminal window, navigate into our directory usingcd python/src/game_of_life. Then run your code by executingpython3 main.py(macOS/Linux) orpython main.py(Windows).

As a result of running our code, you should see a file named rPentomino.png appear in the output folder, shown in the figure below.

Improving our automaton visualization

Let’s add a little bit of flavor to our automaton drawing, by drawing the cells as circles. First, recall the innermost block of draw_game_board(), reproduced below.

# only draw the cell if it's alive

if board[i][j]:

x = j * cell_width

y = i * cell_width

rect = pygame.Rect(int(x), int(y), cell_width, cell_width)

pygame.draw.rect(surface, white, rect)

If board[i][j] is alive, then this code draws a white circle centered in the cell. The top-left corner of the cell is at (j * cell_width, i * cell_width), so to center the circle inside the cell, we add cell_width / 2 to both the x and y coordinates. The radius of the circle is cell_width / 2 so that it exactly fits within the cell.

We are now ready to replace the innermost if statement in draw_game_board() with the following code:

if board[i][j]:

# set coordinates of the cell's center

x = j * cell_width + cell_width / 2

y = i * cell_width + cell_width / 2

pygame.draw.circle(surface, white, (int(x), int(y)), int(cell_width/2))

After running our code once again, we obtain the illustration below. The circles are nice, but the cells touch, which will make the cells tricky to view when we transition to animations.

Let’s reduce the radius of the circle by a bit by multiplying it by a scaling factor, and defining these variables outside of the for-loops to avoid recomputing the values. We adjust draw_game_board() as follows.

def draw_game_board(board: GameBoard, cell_width: int) -> pygame.Surface:

"""

Draw a single GameBoard as a pygame.Surface.

Args:

board (GameBoard): A 2D list of booleans representing the game state

(True = alive cell, False = dead cell).

cell_width (int): Pixel width of each cell in the drawing.

Returns:

pygame.Surface: A surface with the GameBoard visually rendered,

where alive cells are drawn as white circles and dead cells remain background-colored.

"""

if not isinstance(cell_width, int) or cell_width <= 0:

raise ValueError("cell_width must be a positive integer.")

if not isinstance(board, list) or len(board) == 0:

raise ValueError("board must be a non-empty 2D list.")

width = count_cols(board) * cell_width

height = count_rows(board) * cell_width

# create a drawing surface

surface = pygame.Surface((width, height))

# declare some color variables

dark_gray = (60, 60, 60)

white = (255, 255, 255)

# set the background color of the board to gray

surface.fill(dark_gray)

scaling_factor = 0.8

radius = scaling_factor * cell_width / 2

# fill in the alive squares

for i in range(len(board)):

for j in range(len(board[0])):

if board[i][j]:

x = j * cell_width + cell_width / 2

y = i * cell_width + cell_width / 2

pygame.draw.circle(surface, white, (int(x), int(y)), int(radius))

# return the surface with the board drawn on it

return surface

Running our main.py code this time produces the following image.

Now that draw_game_board() is improved, we are ready to draw more complicated boards. For example, run your code after changing def main() as follows to draw the dinner table oscillator, which is shown in the figure below on the left.

def main():

pygame.init()

# read the board from file

dinner_table = read_board_from_file("boards/dinnerTable.csv")

cell_width = 20

surface = draw_game_board(dinner_table, cell_width)

# Save surface as PNG

filename = "output/dinnerTable.png"

pygame.image.save(surface, filename)

pygame.quit()

STOP: Run your code once again after reading in the Gosper gun (gosperGun.csv) to draw the Gosper gun shown in the figure below on the right.

Drawing multiple Game of Life boards

Now that we have written a function to draw a single board, we will also write a draw_game_boards() function in drawing.py that takes a list of GameBoard objects boards and an integer cell_width as input and that returns a list of pygame.Surface objects corresponding to calling draw_game_boards() on each GameBoard in boards. This function will come in handy in the next code along, when we will write a function returning a list of GameBoard variables as a result of simulating the Game of Life over multiple generations, and after calling draw_game_board() on this list, we will generate an animated video showing the changes in the automaton over time.

def draw_game_boards(boards: list[GameBoard], cell_width: int) -> list[pygame.Surface]:

"""

Draw multiple GameBoard objects as pygame.Surface images.

Args:

boards (list[GameBoard]): A list of GameBoard objects,

where each board is a 2D grid of booleans (True = alive, False = dead).

cell_width (int): Pixel width of each cell in the drawing.

Returns:

list[pygame.Surface]: A list of pygame.Surface objects,

each corresponding to the rendering of one GameBoard.

"""

if not isinstance(cell_width, int) or cell_width <= 0:

raise ValueError("cell_width must be a positive integer.")

if not isinstance(boards, list) or len(boards) == 0:

raise ValueError("boards must be a non-empty list of GameBoard objects.")

result = []

for board in boards:

result.append(draw_game_board(board, cell_width))

return result

Looking ahead

Now that we can visualize the Game of Life, we are ready to implement the automaton, so that we can form multiple generations for any initial game board. Join us to do so in the next code along!