Learning objectives

In this code along, we will discuss reading in a system of heavenly bodies from file, and producing an animation showing a sequence of time steps of this system over time. Once we have done so, we will be prepared to write a physics engine in the next code along to simulate the effects of gravity on our system.

Setup

To complete this code along and the next code along on building a physics engine for our gravity simulator, we will need starter code.

We provide this starter code as a single download gravity.zip. Download this code here, and then expand the folder. Move the resulting gravity directory into your python/src source code directory.

The gravity directory has the following structure:

data: a directory containing.txtfiles that represent different initial systems that we will simulate.output: an initially empty directory that will contain images and .mp4 videos that we draw.datatypes.py: a file that contains type declarations.gravity.py: a file that will contain functions that we will write in the next code along for implementing our physics engine.custom_io.py: a file that contains code for reading in a system of heavenly bodies from file.drawing.py: a file that will contain code for drawing a system to file and creating animations over multiple time steps.main.py: a file that will containdef main(), where we will call functions to read in systems, run our gravity simulation, and draw the results.

Code along summary

Organizing data

We begin with datatypes.py, which will store all our class declarations. As we saw in the core text, in the same way that we design functions top-down, we can design objects top-down as well. We recall the language-neutral type declarations for our gravity simulator below, starting with a Universe object, which contains an array of Body objects as one of its fields.

type Universe

bodies []Body

width float

gravitationalConstant float

In turn, we define a Body object, which includes multiple fields involving OrderedPair objects, as shown below.

type Body

name string

mass float

radius float

position OrderedPair

velocity OrderedPair

acceleration OrderedPair

red int

green int

blue int

type OrderedPair

x float

y float

To implement these ideas, we will apply what we learned in the previous code along about class declarations. We start with the Universe class, which will make the gravitational constant into a class field, since this constant applies to every Universe object that we will work with. We set its default value equal to 6.674 · 10-11, which can always be updated later.

class Universe:

"""

Represents the entire simulation environment.

"""

gravitational_constant: float = 6.674e-11 # Default; can be overridden

# to fill in

The other two attributes of Universe are instance attributes and are a list of Body objects and the width of the Universe (in meters), which we will use to establish the boundaries of a square region that we will render in visualizations. We also provide some parameter checks in our constructor to ensure that attributes are within allowable ranges when an instance of a Universe object is initialized. Note that we don’t provide a default for the bodies attribute, for reasons we will discuss in a later chapter.

class Universe:

"""

Represents the entire simulation environment.

"""

gravitational_constant: float = 6.674e-11 # Default; can be overridden

def __init__(self, bodies: list[Body], width: float = 1000.0):

if not isinstance(bodies, list) or not all(isinstance(b, Body) for b in bodies):

raise TypeError("bodies must be a list of Body objects.")

if not isinstance(width, (int, float)) or width <= 0:

raise ValueError(f"width must be a positive number, got {width}")

self.bodies = bodies

self.width = float(width)

Note: We omit__repr__throughout this code along, but you can find this function for each class declaration in our starter code.

We next define a Body class, where the position, velocity, and acceleration attributes are each represented by an OrderedPair object. Note how many parameter checks we have because we have so many attributes.

class Body:

"""

Represents a celestial body within the simulation universe.

"""

def __init__(

self,

name: str,

mass: float,

radius: float,

position: OrderedPair,

velocity: OrderedPair,

acceleration: OrderedPair,

red: int,

green: int,

blue: int

):

# Name

if not isinstance(name, str) or not name.strip():

raise ValueError("Body name must be a non-empty string.")

# Physical properties

if not isinstance(mass, (int, float)) or mass <= 0:

raise ValueError(f"Mass must be a positive number, got {mass}")

if not isinstance(radius, (int, float)) or radius < 0:

raise ValueError(f"Radius must be a non-negative number, got {radius}")

# Vectors

for arg, label in ((position, "position"), (velocity, "velocity"), (acceleration, "acceleration")):

if not isinstance(arg, OrderedPair):

raise TypeError(f"{label} must be an OrderedPair, got {type(arg).__name__}")

# Color

for c, channel in ((red, "red"), (green, "green"), (blue, "blue")):

if not isinstance(c, int):

raise TypeError(f"Color component {channel} must be int, got {type(c).__name__}")

if not (0 <= c <= 255):

raise ValueError(f"Color component {channel} must be in range [0, 255], got {c}")

self.name = name

self.mass = float(mass)

self.radius = float(radius)

self.position = position

self.velocity = velocity

self.acceleration = acceleration

self.red = red

self.green = green

self.blue = blue

Finally, we provide our OrderedPair object, which has two instance attributes x and y.

class OrderedPair:

"""

Represents a 2D vector or coordinate pair (x, y).

Attributes:

x: The x-coordinate or horizontal component (float).

y: The y-coordinate or vertical component (float).

"""

def __init__(self, x: float = 0.0, y: float = 0.0):

if not isinstance(x, (int, float)):

raise TypeError(f"x must be a number (int or float), got {type(x).__name__}")

if not isinstance(y, (int, float)):

raise TypeError(f"y must be a number (int or float), got {type(y).__name__}")

self.x: float = float(x)

self.y: float = float(y)

Reading a universe from file

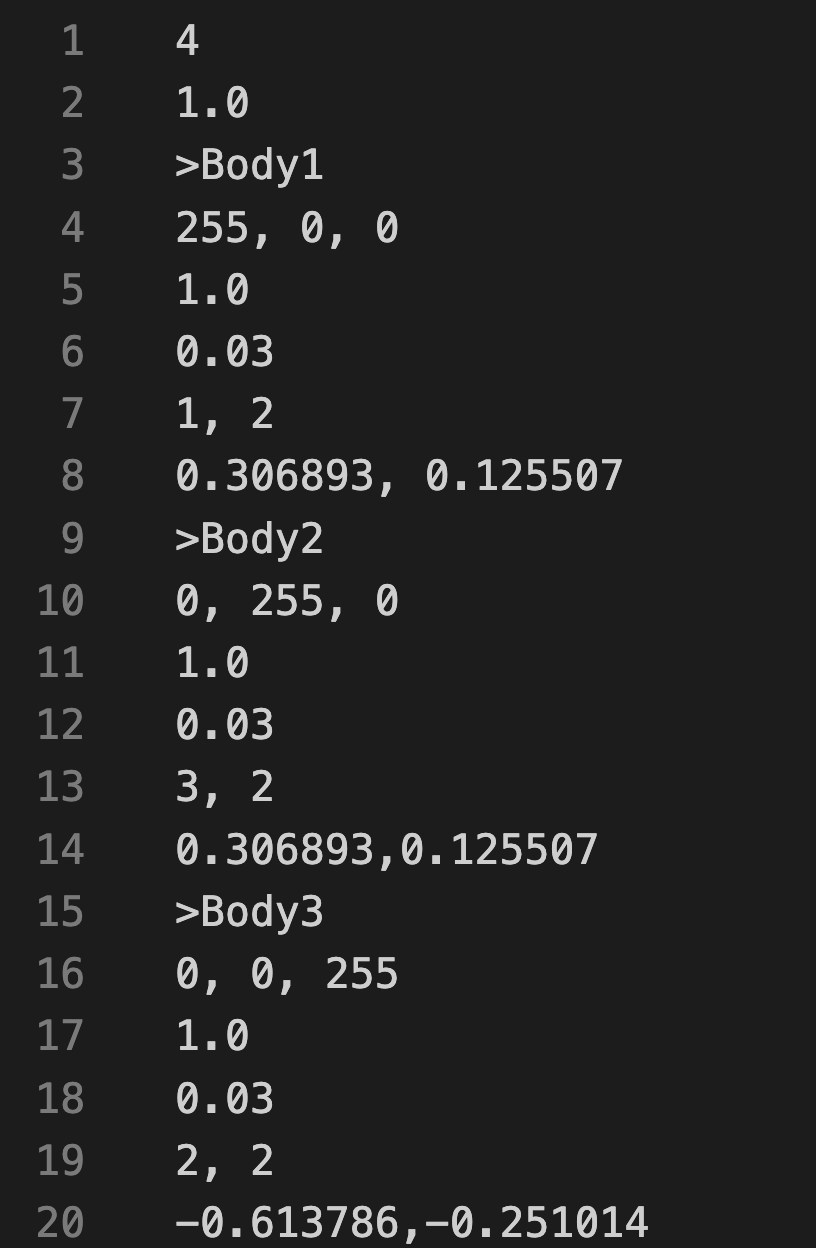

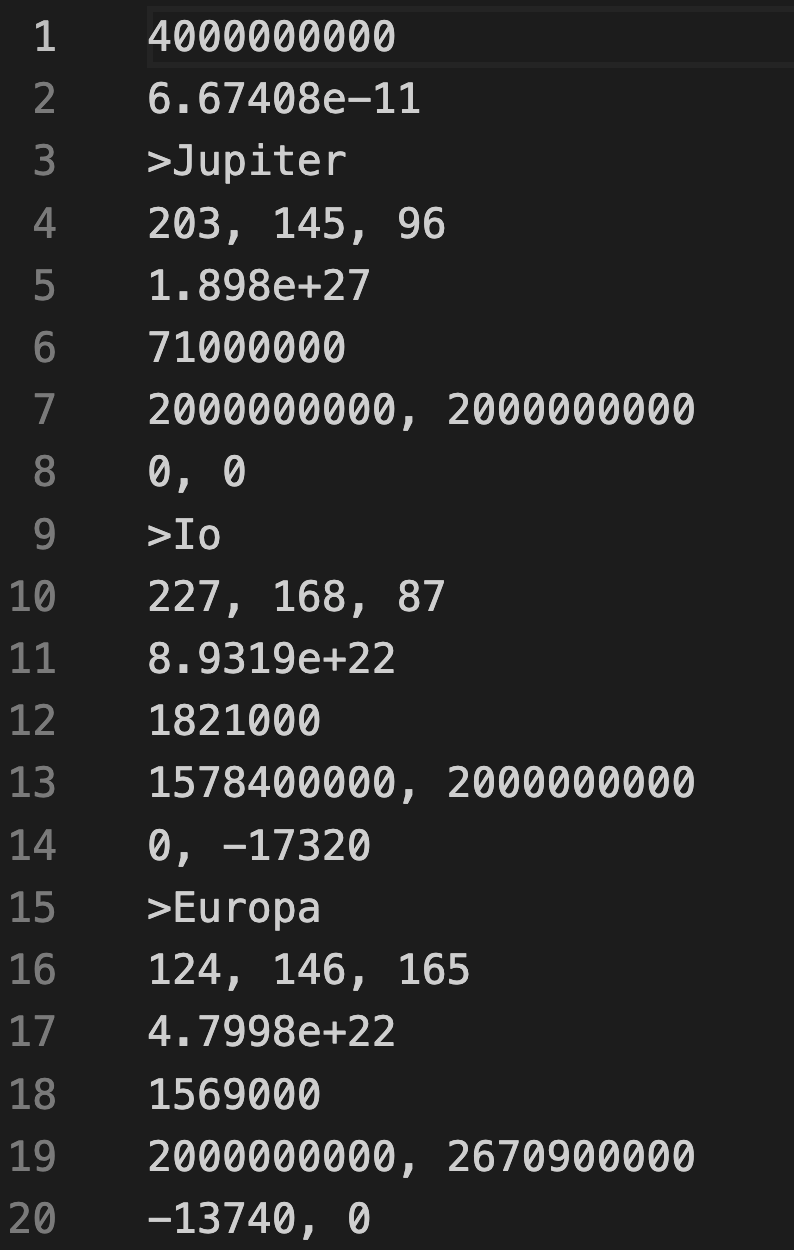

The data directory contains a collection of plain text files, one for each universe that we will model. For example, the figures below show butterfly.txt on the left (which represents a three-body system) and the first 20 lines of jupiterMoons.txt on the right (which represents Jupiter and four moons).

The first line of each universe data file specifies the width of the universe, and the second line stores the gravitational constant. The bodies of the universe are then given in subsequent blocks, where each block consists of six lines:

- >Name of the body

- RGB color (three integers in the range 0–255)

- Mass (in kg)

- Radius (in m)

- Initial position components (x, y)

- Initial velocity components (vx, vy)

Note that the gravitational constant for butterfly.txt (and in fact all the three-body systems in our example) is standardized to 1 to allow the simulation values to be somewhat small; they could be scaled up to have the same gravitational constant as is observed in our universe.

Our primary function in custom_io.py is read_universe(), which takes as input a string filename. This function parses the file contained at the location given by filename into a Universe object that it returns. This function, along with two subroutines that it calls, is provided in the starter code.

Converting to video

We now turn to drawing.py, which contains our code for drawing Universe objects to pygame.Surface objects. Before writing this code, we point out that we provide a function save_video_from_surfaces(), which takes as input a list of pygame.Surface objects as well as a file name (along with a few other parameters related to video rendering), and produces an .mp4 from the list at the desired file name location. This function and its subroutine are shown below.

def pygame_surface_to_numpy(surface: pygame.Surface) -> np.ndarray:

"""

Convert a pygame Surface to a NumPy RGB array of shape (H, W, 3).

This is handy for exporting frames via imageio/moviepy later.

"""

if not isinstance(surface, pygame.Surface):

raise TypeError("surface must be a pygame.Surface")

return pygame.surfarray.array3d(surface).swapaxes(0, 1)

Animating a system and drawing a universe to a canvas

We next turn to our highest-level drawing function animate_system(), which takes as input a list of Universe objects time_points as well as an integer canvas_width. It returns a list of pygame.Surface objects representing our renderings of each Universe in time_points, where each such virtual canvas is canvas_width pixels wide and canvas_width pixels tall. To do so, it calls a subroutine draw_to_canvas() that takes as input a single Universe object u as well as canvas_width and returns the pygame.Surface object corresponding to rendering u.

def animate_system(

time_points: list[Universe],

canvas_width: int

) -> list[pygame.Surface]:

"""

Render every snapshot of the Universe into pygame surfaces.

Delegates the drawing to draw_to_canvas(u, canvas_width).

"""

if not isinstance(time_points, list):

raise TypeError("time_points must be a list of Universe objects")

if len(time_points) == 0:

raise ValueError("time_points must not be empty")

for u in time_points:

if not isinstance(u, Universe):

raise TypeError("all elements of time_points must be Universe objects")

if not isinstance(canvas_width, int) or canvas_width <= 0:

raise ValueError("canvas_width must be a positive integer")

surfaces = []

for u in time_points:

surface = draw_to_canvas(u, canvas_width)

surfaces.append(surface)

return surfaces

We next write draw_to_canvas(). First, we create the surface and fill it with a white background.

def draw_to_canvas(

u: Universe,

canvas_width: int,

) -> pygame.Surface:

"""

Draw a single Universe snapshot onto a new pygame Surface.

"""

# --- lightweight parameter checks ---

if not isinstance(u, Universe):

raise TypeError("u must be a Universe")

if not isinstance(canvas_width, int) or canvas_width <= 0:

raise ValueError("canvas_width must be a positive integer")

# --- create drawing surface ---

surface = pygame.Surface((canvas_width, canvas_width))

surface.fill((255, 255, 255)) # white background

# to fill in

return surface

Next, we range over all the Body objects in u.bodies to draw each one. After forming a tuple from the red, green, and blue attributes of the current body to represent its color, we need to identify the body’s center and radius on the virtual canvas. To do so, we need to apply a bit of algebra in order to convert the attributes of the body within the bounds of u (a square that is u.width meters wide and u.width meters tall) into the canvas (a square that is canvas_width pixels wide and canvas_width pixels tall). Specifically, we multiply each attribute that we care about (b.position.x, b.position.y, and b.radius) by the ratio canvas_width/u.width to obtain center_x, center_y, and radius, which we need to draw the body on the canvas.

def draw_to_canvas(

u: Universe,

canvas_width: int,

) -> pygame.Surface:

"""

Draw a single Universe snapshot onto a new pygame Surface.

"""

# --- lightweight parameter checks ---

if not isinstance(u, Universe):

raise TypeError("u must be a Universe")

if not isinstance(canvas_width, int) or canvas_width <= 0:

raise ValueError("canvas_width must be a positive integer")

if not isinstance(trails, dict):

raise TypeError("trails must be a dict[int, list[OrderedPair]]")

# --- create drawing surface ---

surface = pygame.Surface((canvas_width, canvas_width))

surface.fill((255, 255, 255)) # white background

# Draw bodies

for b in u.bodies:

color = (b.red, b.green, b.blue)

center_x = int((b.position.x / u.width) * canvas_width)

center_y = int((b.position.y / u.width) * canvas_width)

radius = (b.radius / u.width) * canvas_width

pygame.draw.circle(surface, color, (center_x, center_y), int(radius))

return surface

Running our code to draw universes

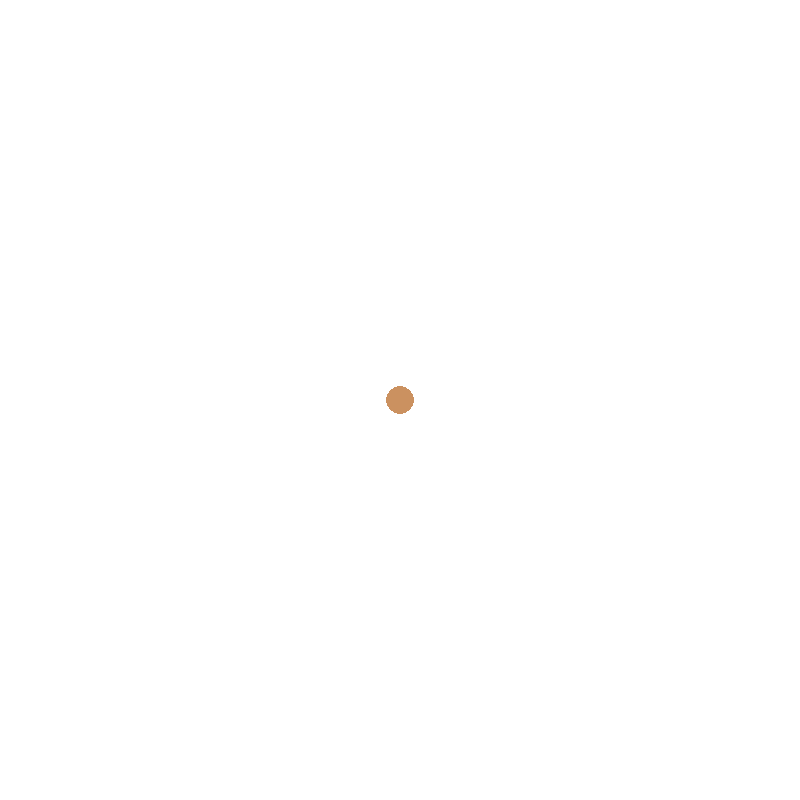

Let’s check that our drawing code is working by using it to draw a couple of sample Universe objects. We first will read and draw the three-body system represented by data/butterfly.txt.

from custom_io import read_universe

from drawing import draw_to_canvas

def main():

canvas_width = 1000

universe = read_universe("data/butterfly.txt")

surface = draw_to_canvas(universe, canvas_width)

pygame.image.save(surface, "output/butterfly.png")

STOP: In a new terminal window, navigate into our directory usingcd python/src/gravity. Then run your code by executingpython3 main.py(macOS/Linux) orpython main.py(Python).

After running our code, we will see the image below appear in the output directory, showing the initial state of the three bodies in the butterfly three-body simulation.

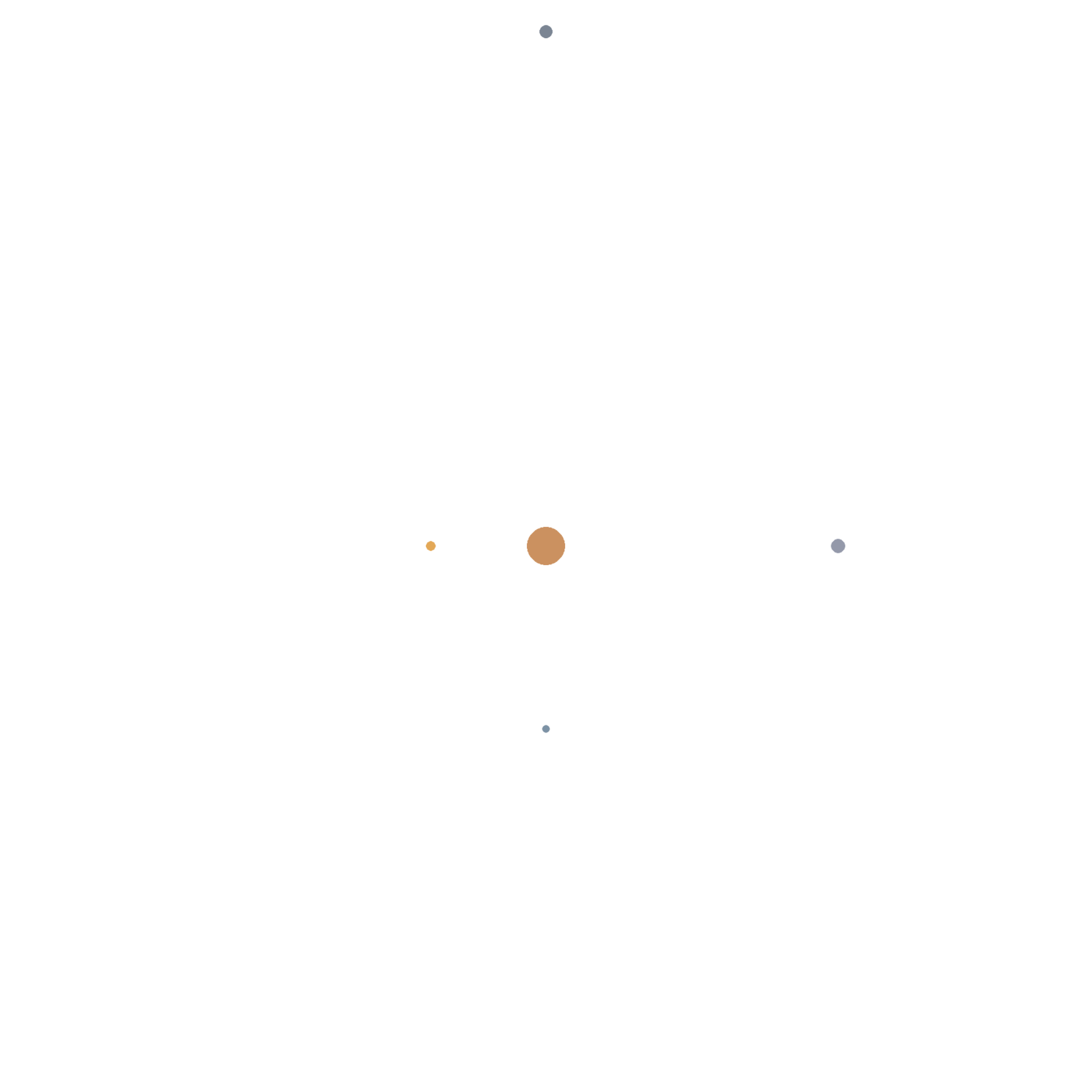

Next, let’s draw the initial state of Jupiter and four of its moons, contained in data/jupiterMoons.txt. Add the following code to main().

from custom_io import read_universe

from drawing import draw_to_canvas

def main():

canvas_width = 1000

universe = read_universe("data/butterfly.txt")

surface = draw_to_canvas(universe, canvas_width)

pygame.image.save(surface, "output/butterfly.png")

universe = read_universe("data/jupiterMoons.txt")

surface = draw_to_canvas(universe, canvas_width)

pygame.image.save(surface, "output/jupiterMoons.png")

When we run our code, we obtain the image below. Jupiter is visible, but where are the moons?

The problem is that Jupiter is so much larger than its moons that when drawn to scale, each moon is less than one pixel wide. To fix this, we will multiply the radius of each moon when it is drawn upon the canvas. To do so, we add a constant called JUPITER_MOON_MULTIPLIER to the top of drawing.py after package imports, and set it equal to 10. This constant’s name may make it seem as though you are texting with your grandparents, but naming a variable with all capitals follows official Python style when we wish to indicate to the user that the value of a variable should never change.

Second, before drawing a Body to our pygame virtual canvas, we check its name to see if it is one of our moons of Jupiter; if so, we multiply the radius used for drawing to the canvas by the JUPITER_MOON_MULTIPLIER constant.

JUPITER_MOON_MULTIPLIER = 10.0

def draw_to_canvas(

u: Universe,

canvas_width: int,

) -> pygame.Surface:

"""

Draw a single Universe snapshot onto a new pygame Surface.

"""

# --- lightweight parameter checks ---

if not isinstance(u, Universe):

raise TypeError("u must be a Universe")

if not isinstance(canvas_width, int) or canvas_width <= 0:

raise ValueError("canvas_width must be a positive integer")

if not isinstance(trails, dict):

raise TypeError("trails must be a dict[int, list[OrderedPair]]")

# --- create drawing surface ---

surface = pygame.Surface((canvas_width, canvas_width))

surface.fill((255, 255, 255)) # white background

# Draw bodies

for b in u.bodies:

color = (b.red, b.green, b.blue)

center_x = int((b.position.x / u.width) * canvas_width)

center_y = int((b.position.y / u.width) * canvas_width)

radius = (b.radius / u.width) * canvas_width

if b.name in ("Io", "Ganymede", "Callisto", "Europa"):

radius *= JUPITER_MOON_MULTIPLIER

pygame.draw.circle(surface, color, (center_x, center_y), int(radius))

return surface

Now when we re-run our code, we will see the moons of Jupiter appear, as shown below.

Looking ahead

Now that we can read in a collection of bodies from file and visualize the positions of these bodies, all that remains is the intermediate step of simulating the effects of gravity over a number of generations. In the next code along, we will build a physics engine to simulate the effects of gravity that will allow us to visualize the movements of heavenly bodies over time.