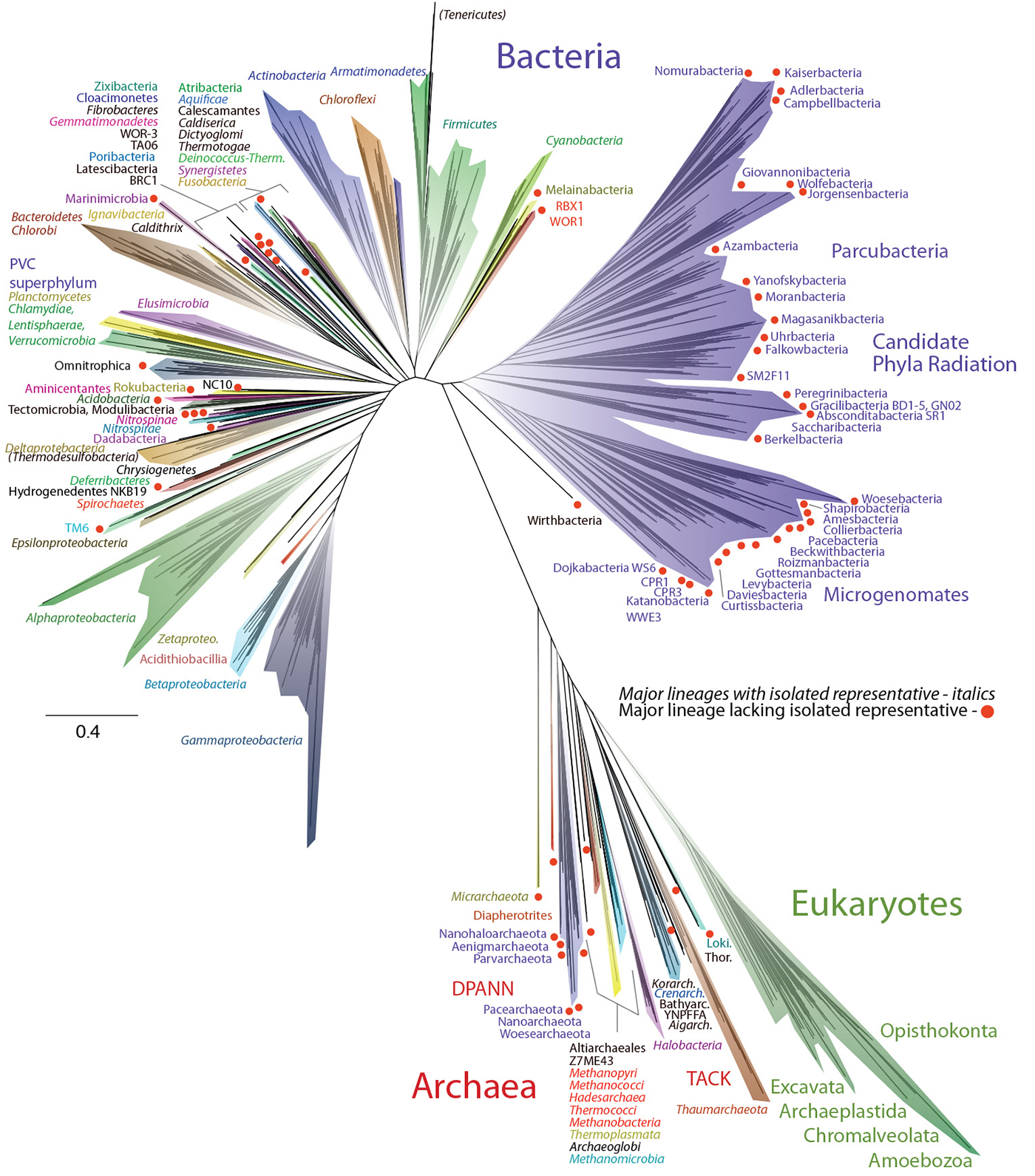

The affinities of all the beings of the same class have sometimes been represented by a great tree. I believe this simile largely speaks the truth. The green and budding twigs may represent existing species; and those produced during former years may represent the long succession of extinct species. At each period of growth all the growing twigs have tried to branch out on all sides, and to overtop and kill the surrounding twigs and branches, in the same manner as species and groups of species have at all times overmastered other species in the great battle for life.

Charles Darwin (On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, 1859)

The world’s fastest outbreak

On February 21, 2003, a Chinese doctor named Liu Jianlun flew to Hong Kong to attend a wedding and checked into Room 911 of the Metropole Hotel. The next day, he became too ill to attend the wedding and was admitted to a hospital. Two weeks later, he was dead.

On his deathbed, Dr. Liu stated that he had recently treated sick patients in Guangdong Province, where a highly contagious respiratory illness had infected hundreds of people. The Chinese government had made brief mention of this incident to the World Health Organization (WHO) but had concluded that the likely culprit was a common bacterial infection. By the time anyone realized the severity of the disease, it was already too late to stop the outbreak.

On February 23, a man who had stayed across the hall from Dr. Liu at the Metropole traveled to Hanoi and died after infecting 80 people. On February 26, a woman checked out of the Metropole, traveled back to Toronto, and died after initiating an outbreak there. On March 1, a third guest was admitted to a hospital in Singapore, where sixteen additional cases of the illness arose within two weeks.

Consider that the Black Death, which killed over a third of all Europeans in the 14th century, took five years to travel from Constantinople to Kiev (see below). In contrast, this mysterious new disease had crossed the Pacific Ocean within a week of entering Hong Kong.

As health officials braced for the impact of the fastest traveling virus in human history, panic set in. Businesses were closed, sick passengers were removed from airplanes, and Chinese officials threatened to execute anyone deliberately spreading the disease. In the process, the mysterious new illness earned a name: severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS.

SARS was deadly, killing close to 10% of those who became sick. But it also struggled to spread within the human population, and it was contained in July 2003 after accumulating fewer than 10,000 confirmed symptomatic cases worldwide.

A new threat emerges

On December 30, 2019, a Chinese ophthalmologist named Li Wenliang sent a WeChat message to fellow doctors at Wuhan Central Hospital, warning them that he had seen several patients with symptoms resembling SARS. He urged his colleagues to wear protective clothing and masks to shield them from this new threat.

The next day, a screenshot of his post was leaked online, and local police summoned Dr. Li and forced him to sign a statement that he had “severely disturbed public order”. He then returned to work, treating patients in the same Wuhan hospital.

Meanwhile, WHO received reports of multiple pneumonia cases from the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission and activated a support team to assess the new disease. WHO declared on January 14 that local authorities had seen “no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission of the novel coronavirus”. But once again, it was already too late.

Throughout January, the virus silently raged through China as Lunar New Year celebrations took place within the country, and it spread to both South Korea and the United States. By the end of the month, the disease was in 20 countries, earning a name in the process: coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

As for Dr. Li? Despite warning against the risk of the new virus, he contracted COVID-19 from one of his patients on January 8. He continued working until he was forced to be admitted to the hospital on January 31. Within a week, he was dead, one of the first of millions of COVID-19 casualties.

The evolution of SARS

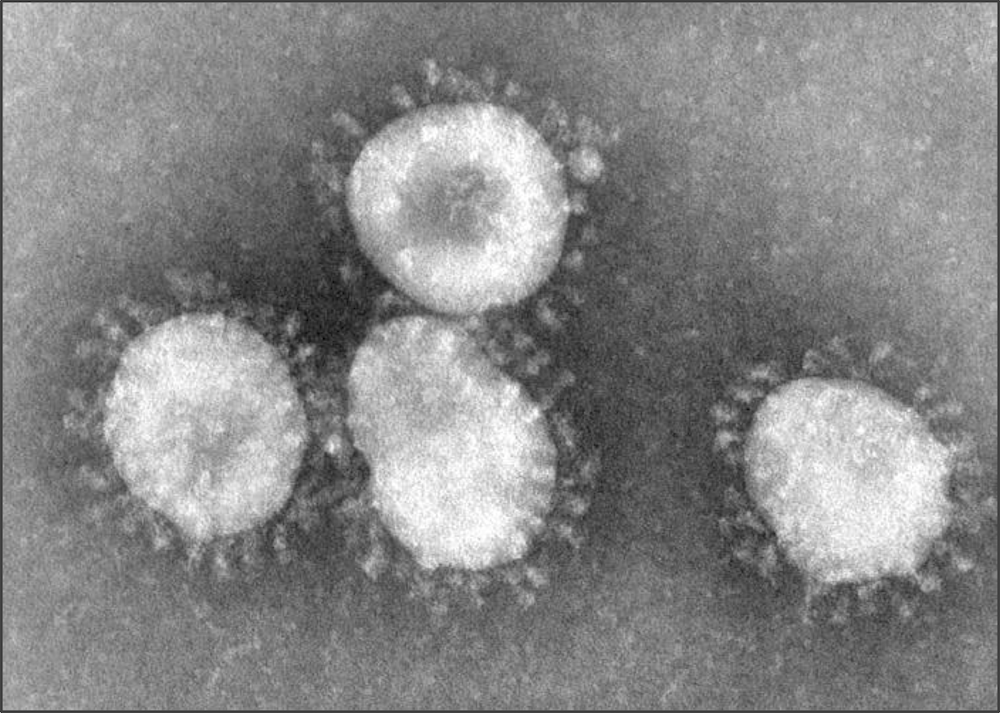

The viruses causing the two outbreaks, SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and SARS coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) are both coronaviruses, which means that their outer membranes are covered in a layer of spike proteins that cause them to look like the sun’s corona during an eclipse (see figure below). Coronaviruses infect the respiratory tracts of mammals and birds and typically cause only minor problems, like the common cold. Before SARS, no one believed that a coronavirus could wreak such havoc.

Coronaviruses, influenza viruses, and HIV are all RNA viruses, meaning that they possess RNA instead of DNA. RNA replication has a higher error rate than DNA replication, and so RNA viruses are capable of mutating more quickly into divergent strains. The rapid mutation of RNA viruses explains why the flu shot changes from year to year and why HIV has proven so difficult to vaccinate against.

The study of coronaviruses leads to a number of questions. How did each virus cross the species barrier to humans? How did SARS spread around the world? And how have researchers identified new SARS-CoV-2 variants?

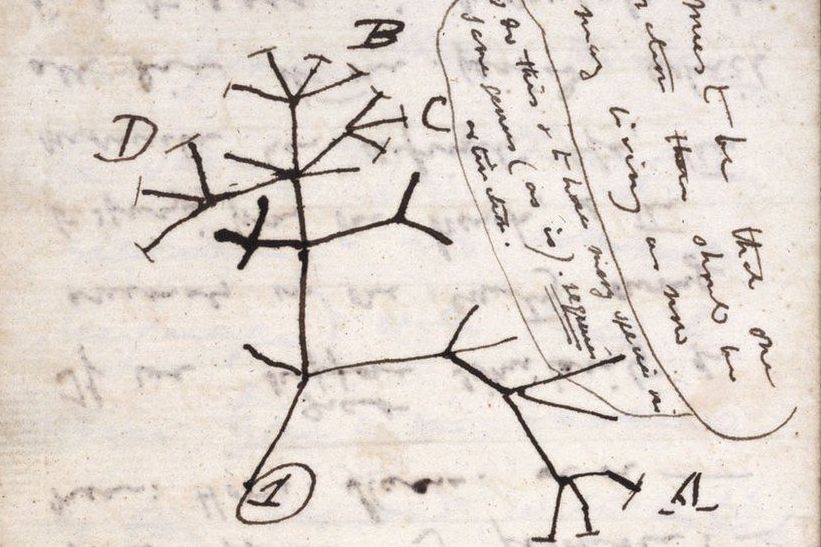

These questions ultimately rely on the problem of constructing evolutionary trees of coronaviruses, in which present-day species are shown at the “leaves” of the tree and connections represent evolutionary relationships. Evolutionary trees date to 1837, when Charles Darwin reasoned that if species are evolving, then over time they would branch out into a tree structure (his scribble is shown in the figure below).

Evolutionary trees have become one of the most common models used in biology, and they have progressed far beyond Darwin’s work. Whereas Darwin thought about evolution in terms of visible eukaryotic species like plants and animals, a tree of life constructed from genomic data taken from many species demonstrates that Earth is a bacterial planet that you and I merely inhabit (see figure below).

Yet what algorithm should we use to construct an evolutionary tree like the one in the figure above? In this chapter, we will see that this is a more complicated question that we might imagine, which is why entire textbooks have been written on evolutionary tree algorithms. In so doing, we will deepen our study of object-oriented programming and implement one of the most famous algorithms used for making evolutionary trees.