Code along video

Although we strongly suggest coding along with us by following the video above, you can find completed code from the code along in our course code repository.

Note: Each chapter of Programming for Lovers comprises two parts. First, the “core text” presents critical concepts at a high level, avoiding language-specific details. The core text is followed by “code alongs,” where you will apply what you have learned while learning the specifics of the language syntax.

Learning objectives

In the core text, we gained an appreciation for the pitfalls of generating pseudorandom numbers. In this code along, we will see how Python implements built-in functions for pseudorandom number generation and then apply these functions to the context of simulating dice.

Recall that we introduced the following function for rolling a single die.

RollDie()

roll ← RandIntn(6)

return roll + 1

The function RollDie() relies on a function RandIntn() that takes as input a positive integer n and returns a pseudorandom number between 0 and n – 1, which we can assume is built into programming languages so that we do not need to focus on the sinful details of pseudorandom number generation.

Setup

Create a new folder called dice in your python/src directory, and then create a new file within the python/src/dice folder called main.py, which we will edit in this lesson.

To work with pseudorandom number generation, we will need to work with Python’s built-in random module. Your main.py file should therefore have the following code, which starts with import random.

import random

def main():

print("Rolling dice and playing craps.")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Code along summary

Built-in pseudorandom number generation functions

In the core text, we introduced three functions on the level of pseudocode for generating pseudorandom numbers.

RandInt(): takes no inputs and returns a pseudorandom integer from the range of all possible integers that the language can store in memory.RandIntn(): takes as input a non-negative integer n and returns a pseudorandom integer between 0 and n – 1, inclusively.RandFloat(): takes no inputs and returns a pseudorandom decimal number in the range [0, 1).

Python doesn’t provide support for RandInt() because in Python, unlike many other languages, there is no bound on how large or small an int can be, and so an implementation of RandInt() would need to return one of infinitely many possible values. In this course, we will just need the latter two functions.

Python implements RandIntn() in a couple of ways, but we will use one consistently through this course: random.randrange(), which takes as input two integer parameters a and b and returns a pseudorandom integer between a and b-1, inclusively.

As for generating a float in the range [0, 1), Python provides a function random.random().

Let’s print the result of calling each of these two functions on sample inputs.

import random

def main():

print("Rolling dice and playing craps.")

print(random.randrange(0,10)) # prints integer between 0 and 9, inclusively

print(random.random()) # prints decimal in range [0, 1)

STOP: In a new terminal window, navigate into our directory usingcd python/src/dice. Then run your code by executingpython3 main.py(macOS/Linux) orpython main.py(Python).

Let’s run our code multiple times by running it multiple times. As you might expect, we obtain different results each time the code is run.

Seeding Python’s PRNG

Yet for a few years, the above code would always produce the same three numbers. To understand why, we recall a fact that we learned when we first introduced PRNGs.

As we learned in the core text, any pseudorandom number generator (PRNG) follows a process that is not truly random. As a result, Python’s PRNG must be initialized with some value, called the seed of the PRNG. We can change this seed ourselves by invoking the function random.seed(), which takes an integer as input and returns no outputs. Let’s add a call to random.seed() to def main(), before we ever generate any random numbers.

def main():

print("Rolling dice and playing craps.")

random.seed(0) # seeding PRNG with an arbitrary value.

print(random.randrange(0,10)) # prints integer between 0 and 9, inclusively

print(random.random()) # prints decimal in range [0, 1)

STOP: Re-execute the terminal commandpython3 main.py. Execute the code several times; what do you find?

Regardless of how many times this code is run, we obtain the same two numbers: 6 and 0.04048437818077755. In fact, for the first 3 years of Python’s random module’s existence, we would always obtain these numbers in a program the first time we called random.randrange(0,10) and random.random(). This is because, behind the scenes, Python would automatically call random.seed(0). So, what changed?

Starting with version 2.3, Python’s random module began automatically seeding its built-in PRNG based on the current time. We could do this ourselves using the "time" package as follows, but this code is not necessary, and we will remove it going forward in this code along.

import random

import time

def main():

print("Rolling dice and playing craps.")

random.seed(time.time_ns()) # seed PRNG based on time; this line is not necessary!

print(random.randrange(0,10)) # prints integer between 0 and 9, inclusively

print(random.random()) # prints decimal in range [0, 1)

Note: Even though we won’t manually seed in this course, manual seeding is very helpful for testing. For example, if you want to verify the output of a function that uses pseudorandom number generation across multiple machines, calling random.seed(0) before running the code ensures that all machines produce the same sequence of results.

Note: If you ever decide to callrandom.seed(), remember that you only need to seed a PRNG once. That is, your program should probably only callrandom.seed()once indef main()outside of any loops and before any calls to functions that generate pseudorandom numbers. Once the seed is set, the sequence of numbers you generate will change.

Rolling a single die

We are now ready to implement roll_die(). At the level of pseudocode, we needed to generate a pseudorandom integer between 0 and 5, inclusively, and then add 1.

RollDie()

roll ← RandIntn(6)

return roll + 1

However, Python gives the shortcut of generating a number between 1 and 6 directly by calling random.randrange(1, 7).

def roll_die() -> int:

"""

Simulates the roll of a die.

Returns:

- int: A pseudorandom integer between 1 and 6, inclusively.

"""

return random.randrange(1, 7)

Let us simulate rolling a single die 10 times. Add the following to main(), and run your code again. You will see ten die rolls printed to the console.

def main():

# code omitted for clarity

for _ in range(10):

print("Die roll:", roll_die())

Rolling two (or multiple) dice

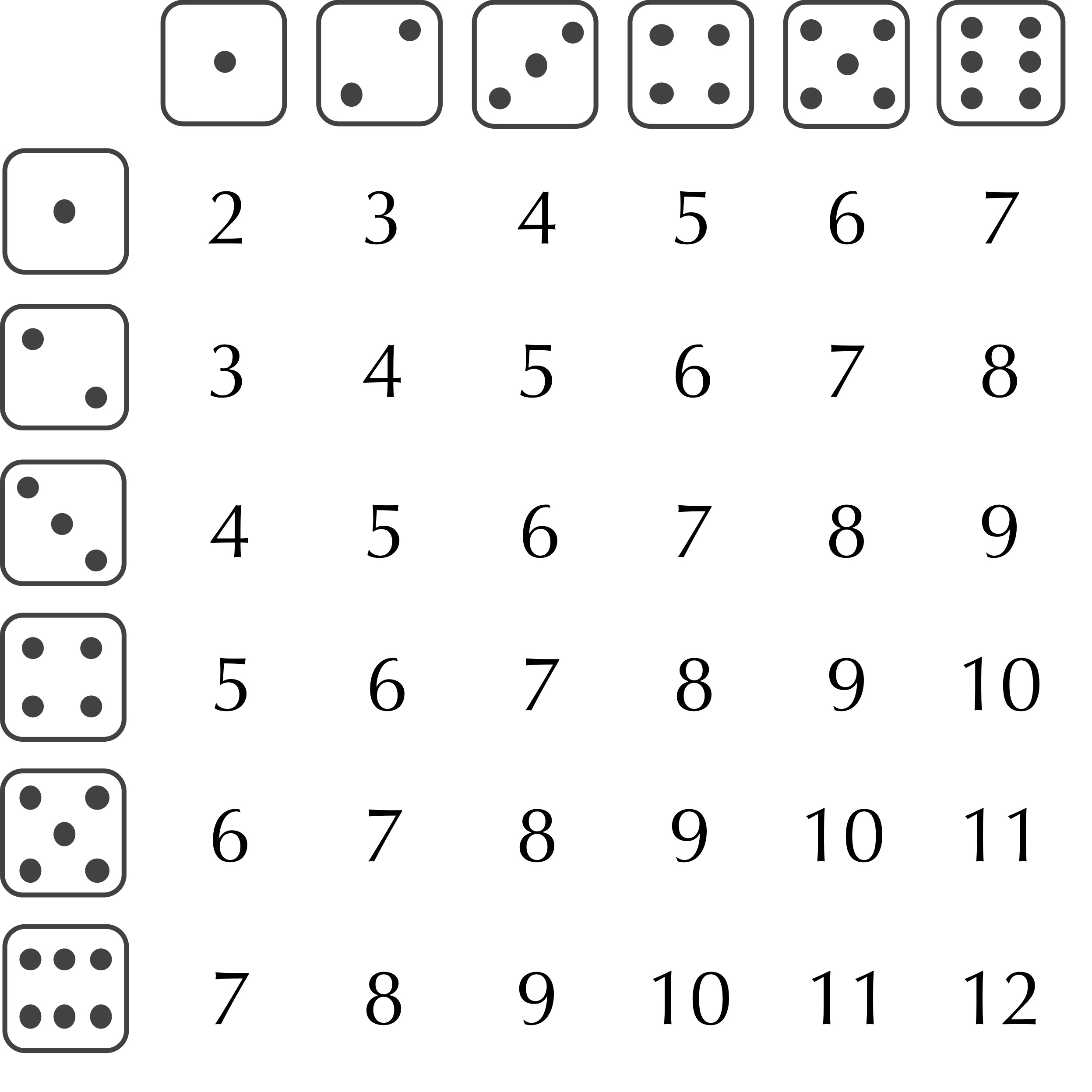

As we mentioned in the core text, one way of simulating the roll of two dice is to consult a table telling us how many of the 36 possibilities for the values on two dice correspond to each possible value of the sum (figure reproduced below). This table tells us that the two dice sum to 2 with probability 1/36, sum to 3 with probability 2/36, sum to 4 with probability 3/36, and so on.

When faced with a problem in which a collection of events have probabilities summing to 1, we can simulate choosing one of these events by dividing the number line between 0 and 1 into segments whose lengths correspond to the probabilities. We can then generate a random number between 0 and 1, and assign an event based on the segment to which this number is assigned. In this particular case, a number between 0 and 1/36 would be assigned a dice roll summing to 2, a number between 1/36 and 3/36 would be assigned a dice roll summing to 3, a number between 3/36 and 6/36 would be assigned a dice roll summing to 4, and so on, allowing us to write a sum_two_dice() function as follows.

def sum_two_dice() -> int:

"""

Simulates the sum of two dice.

Returns:

- int: The simulated sum of two dice (between 2 and 12).

"""

roll = random.random()

if roll < 1.0 / 36.0:

return 2

elif roll < 3.0 / 36.0:

return 3

elif roll < 6.0 / 36.0:

return 4

This function will be very long, and imagine the ramifications of needing to add a third, fourth, or fifth die; we would find ourselves writing if statements forever.

Fortunately, we are not studying mathematics, but rather computer science, a domain in which laziness has long proven to be a virtue. To roll two dice, why not simply simulate the roll of one die twice! As a result, our sum_two_dice() function can be written in a single line.

def sum_two_dice() -> int:

"""

Simulates the sum of two dice.

Returns:

- int: The simulated sum of two dice (between 2 and 12).

"""

return roll_die() + roll_die()

Better yet, our observation allows us to generalize our function to sum the rolls of an arbitrary number of dice by adding an integer parameter num_dice.

def sum_dice(num_dice: int) -> int:

"""

Simulates the process of summing n dice.

Parameters:

- num_dice (int): The number of dice to sum.

Returns:

- int: The sum of num_dice simulated dice.

"""

total = 0

for _ in range(num_dice):

total += roll_die()

return total

To conclude, we will update main() to roll two dice for a few trials. Run your code again, and you should find that all trials result in integers between 2 and 12.

def main():

# code omitted for clarity

for _ in range(10):

print("Rolling two dice gives:", sum_dice(2))

Looking ahead

Now that we can roll two dice, we are ready to simulate a game involving dice. In the next code along, we will simulate the casino game of craps, and then use Monte Carlo simulation to estimate the game’s house edge.

Check your work from the code along

We now provide autograders in the window below (or via a direct link) allowing you to check your work for the following functions:

roll_die()sum_dice()