Defining a Universe object

We will use top-down thinking to design objects for our gravity simulator. That is, although we know that we will need a Body object to represent heavenly bodies, we start by planning a Universe object. This object should contain an array of Body objects as one of our fields, but we will provide additional fields.

type Universe

bodies []Body

We will model a Universe on an infinite two-dimensional plane; adding a third dimension will not make our physics simulation more challenging, but it will make visualizing the gravity simulation more difficult. For that matter, although the plane is infinite, we will only be able to visualize a finite window of this plane when rendering a visualization. We will therefore establish a rendering window as a square whose width is a Universe field width.

type Universe

bodies []Body

width float

Finally, in the next lesson, we will say more about the physics engine that we will build, which depends upon a gravitational constant that dictates the strength of gravity between any two bodies in the universe. Establishing this gravitational constant as a Universe field will allow us to play around with the force of gravity later by changing this field.

type Universe

bodies []Body

width float

gravitationalConstant float

Establishing the fields of a heavenly body

As for a Body object, we will first assign it a name, like "Trisolaris", "Europa", or "Earth".

type Body

name string

We also should assign a Body a mass and a radius.

type Body

name string

mass float

radius float

Thinking ahead to building a physics engine, we will need to maintain the position of each Body in two-dimensional space, as well as its velocity and acceleration. We will say more about this in the next section, but both velocity and acceleration will be represented in terms of their x- and y-components. As a result, position, velocity, and acceleration can each be represented as an ordered pair, which we define as its own object.

type Body

name string

mass float

radius float

position OrderedPair

velocity OrderedPair

acceleration OrderedPair

type OrderedPair

x float

y float

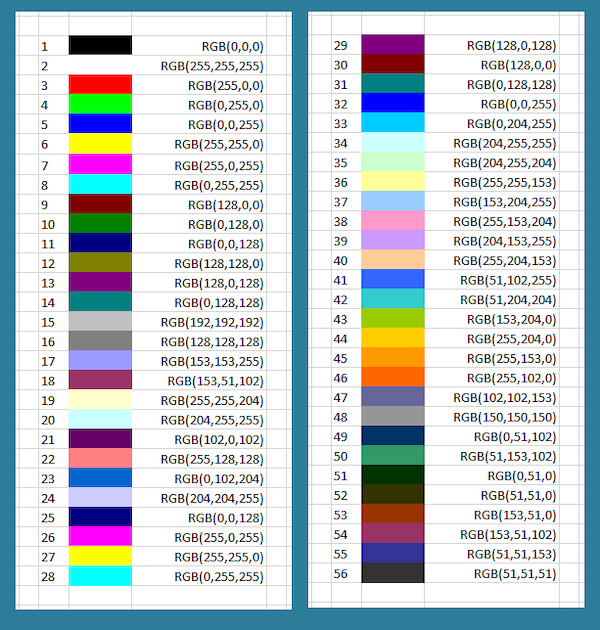

Finally, we add a color attribute to a Body. As we saw in the last chapter’s graphics code alongs, every rectangular pixel on a computer screen emits a single color formed as a mixture of differing amounts of the three primary colors of light: red, green, and blue (hence the acronym “RGB”). We can therefore represent the intensity of each primary color in a pixel as an integer between 0 and 255, inclusively, with larger integers corresponding to greater intensities. The figure below shows a collection of colors along with triples of integers corresponding to their RGB representations.

We now complete our implementation of a Body by adding three integer fields corresponding to each color channel.

type Body

name string

mass float

radius float

position OrderedPair

velocity OrderedPair

acceleration OrderedPair

red int

green int

blue int

Starting our implementation design

Now that we have designed the objects for our simulator, let us return to the central problem that we want to solve and state this problem a bit more formally given what we have learned about object-oriented programming.

Gravity Simulator Problem

Input: AUniverseobjectinitialUniverse, an integernumGens, and a a floating-point numbertime.

Output: An arraytimePointsofnumGens + 1Universe objects, wheretimePoints[0]isinitialUniverse, andtimePoints[i]is obtained fromtimePoints[i-1]by approximating the results of the force of gravity over a time interval equal totime(in seconds).

STOP: Try sketching a solution to the Gravity Simulator Problem top-down in pseudocode.

As we have seen before in top-down design, laziness is a virtue. Our highest-level function for solving the Gravity Simulator Problem, SimulateGravity(), delegates most of its work to an UpdateUniverse() function, which takes as input a Universe object u and a decimal time and returns the updated Universe resulting from applying the gravity simulation over a single time interval of time seconds.

SimulateGravity(initialUniverse, numGens, time)

timePoints ← array of numGens+1 Universe objects

timePoints[0] ← initialUniverse

for every integer i between 1 and numGens

timePoints[i] ← UpdateUniverse(timePoints[i-1], time)

return timePoints

As for UpdateUniverse(), it is just as lazy, passing its own work to not one but four subroutines. One such function copies over one Universe object’s fields into a new Universe, whereas we use the other three to update the acceleration, velocity, and position of a single Body object b.

UpdateUniverse(currentUniverse, time)

newUniverse ← CopyUniverse(currentUniverse)

for every body b in newUniverse

b.acceleration ← UpdateAcceleration(newUniverse, b)

b.velocity ← UpdateVelocity(b, time)

b.position ← UpdatePosition(b, time)

return newUniverse

We have now reached a point where we need to understand more about the gritty details of gravity in order to implement our simulator. Has it been a long time since high school? Or perhaps you didn’t learn physics at all, since after all, only 42% of American high school students take a physics course? Either way, let’s do some physics!